And So It Goes

Kurt Vonnegut's GHQ

The Story

Kurt Vonnegut’s first novel, Player Piano, was published in 1952. While well-reviewed, it did not do well commercially. The Vonnegut’s third child, Nanette, was born in 1954, and they needed to increase their income, as writing was not paying the bills.

So Vonnegut decided to design and license a board game.

This, as any board game designer will tell you, was not the best plan.

He drew on his experiences in World War II and designed a two player semi-abstract wargame which he called GHQ, short for General Headquarters. It was played on a standard 8x8 checkerboard, and featured a variety of units including infantry, armor, paratroopers, and artillery. The objective was simple – capture your opponent’s headquarters.

He looked into patenting the game and sent inquiries off to a publisher in late 1956. Eleven months later, in October 1957, the game was rejected. He put the materials into a box and put them away.

Fortunately for him and the Vonnegut family (and for us, of course), his next novels – The Sirens of Titan, Mother Night, and Cat’s Cradle, broke through into the public consciousness and he was financially secure from his writing for the rest of his life.

As far as we know he never looked at GHQ again.

Publication

I first read the broad outlines of this story – basically just that Vonnegut had tried and failed to publish a board game called GHQ before he was famous - back in 2013. I tried to find out more about it, to no avail. I just kept finding the same bare-bones details repeated over and over.

Vonnegut passed away in 2007, and I learned that his papers were being stored at Indiana University. I reached out to them to see if they had any materials I could see, but they said I would need to get permission from the family first.

I am nothing if not persistent, and ultimately I was able to get the necessary permissions, and started to receive scanned documents from IU.

To be able to see these documents in Vonnegut’s handwriting, doodles and all, was magical. They contained five different versions of the rules, along with sketches and notes. It was fascinating to see how the rules evolved over the course of development, and how he changed how the rules were phrased and tried to express them clearly.

As Vonnegut said in one of his letters: “I am a professional writer, and the toughest assignment I ever had was writing the rules for this thing”.

As a rules writer myself, I take great solace in that.

I particularly enjoyed reading his pitch letter. It is, as you would expect, delightfully written. Yet at the same time It is uncanny how it hits so many of the cliches you find in first-time game designer pitches (going to be up there with chess and checkers, enjoyed by friends and neighbors, etc, etc).

I’ve showed it to many publishers, and many of them laugh out loud when they read it

The last mention of GHQ in Vonnegut’s papers is this rejection letter, that he received 11 months after sending off the initial pitch (still not uncommon, unfortunately).

This rejection letter was received by Kurt just a few weeks after his father passed away. I can only imagine how that loss, closely followed by the rejection of GHQ, which he had labored over intensely for years, must have made him despondent.

I’m not surprised that he put GHQ in a box and never took it out again.

The Game

When I pieced together what I thought was Vonnegut’s final version of the rules, I tried it out and discovered it was pretty good. Maybe it wasn’t “the third greatest checkerboard game” as Vonnegut declared, but it was certainly worth pursuing.

I brought it to the Metatopia playtesting convention and had some people try it without knowing the provenance, and they all enjoyed it.

GHQ actually has a number of innovative mechanics, particularly for the 1950’s.

Multiple Action System: Each player gets three actions on their turn, which they can spend as they wish. Tikal (1999) is broadly considered the Eurogame that popularized an Action Point system, but this was forty years earlier.

Zone of Control: In GHQ if you are adjacent to an enemy your movement is restricted, and you are not allowed to move directly to another space adjacent to an enemy. Also, artillery restricts movement. “Zone of Control” is a wargaming staple first named in the 1960’s in Avalon Hill games, but here it is a decade earlier.

Reinforcements: You start GHQ with just five of your eighteen pieces on the board. Each turn you can spend an Action Point to bring any of your units into an empty space on your back row.

Captures: The Infantry and Artillery capture mechanisms are different and innovative. So innovative that explaining the Infantry capture mechanism was the main thing Vonnegut struggled with in the rules. Once you see it in action it makes perfect sense, but it’s hard to express in a rules format.

Ultimately, I reached out to the family and they agreed that it was worth publishing, and that Kurt would be pleased to see it reach an audience at last.

Since this is as much a literary project as a game project, it made sense to reach out to Barnes & Noble about partnering on the publication. They were enthusiastic about the project and are the exclusive retail distribution partner of GHQ in the US.

The Elephant

The elephant in the room for GHQ, and one of the things that makes the game so fascinating, is that Vonnegut was so anti-war throughout his career. Slaughterhouse-Five, published in 1969, is perhaps his most famous work, and is deeply autobiographical about the trauma he suffered during the Second World War, when he was a POW caught in the Allied bombing of Dresden.

The protagonist becomes ‘unstuck in time’ and is constantly shifting between the different periods of his life, including the war. It is a powerful metaphor of post-traumatic stress, and the way the past can suddenly feel just as real as the present. It portrays war as brutal and pointless.

Even his writings that were contemporaneous with the development of GHQ show this attitude about the futility of war. The Sirens of Titan was published in 1959 (GHQ was designed in 1955-1956) and depicts an army from Mars that robs its soldiers and officers of any sort of free will and is intentionally sacrificed for a ‘greater good’.

So why did he design a war game? It definitely isn’t Vonnegut being ironic, as his pitch letter clearly shows. He makes reference to the game being used as part of the curriculum for West Point, or as a way for veterans to show their families what they learned during the war.

There is no trace of irony in any of his work on the game.

GHQ and Sirens of Titan mark the halfway point between the end of the war and the publication of Slaughterhouse-Five. We know that he tried to write Slaughterhouse (which he called “the Dresden book”) beginning in the early 50’s. But he couldn’t figure out how to tell the story and kept throwing it out and starting anew.

It would take many years and other novels before he matured enough as a writer – and as a human – to be able to process his feelings and frame them into a literary structure that amplified the meta nature of the experience. I believe GHQ was part of that process and another way for him to try to express his war experiences through a creative lens.

The Cover

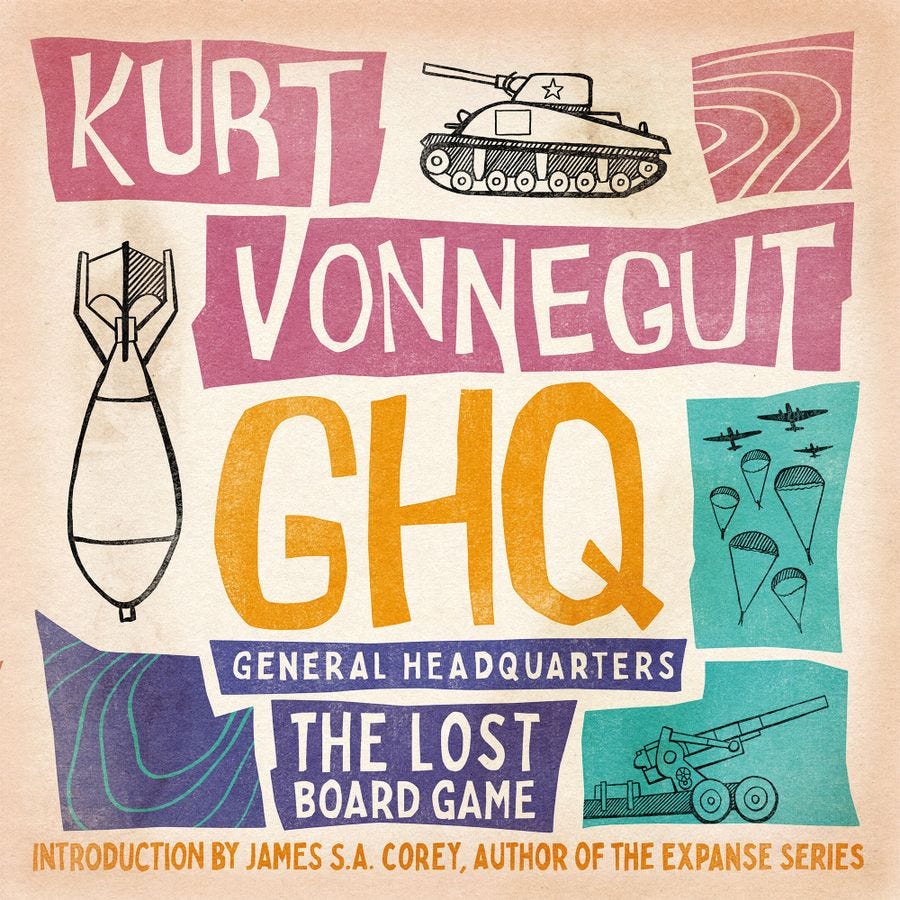

So with that in mind, we had to tackle a thorny question – what do we do with the cover? I was pleased to bring Bill Bricker onto the project as art director. I had worked with Bill on other projects, and knew that he was a huge Vonnegut fan, and would bring the right attitude and attention to the detail GHQ deserved.

We decided early on that we didn’t want to have a battle scene, or a specific war depiction. We felt that perhaps while Vonnegut was serious in his design of a wargame, a straightforward depiction of war was not an appropriate reflection of his overall legacy.

At first we tried a series of ultramodern covers. However, they were a little too stark.

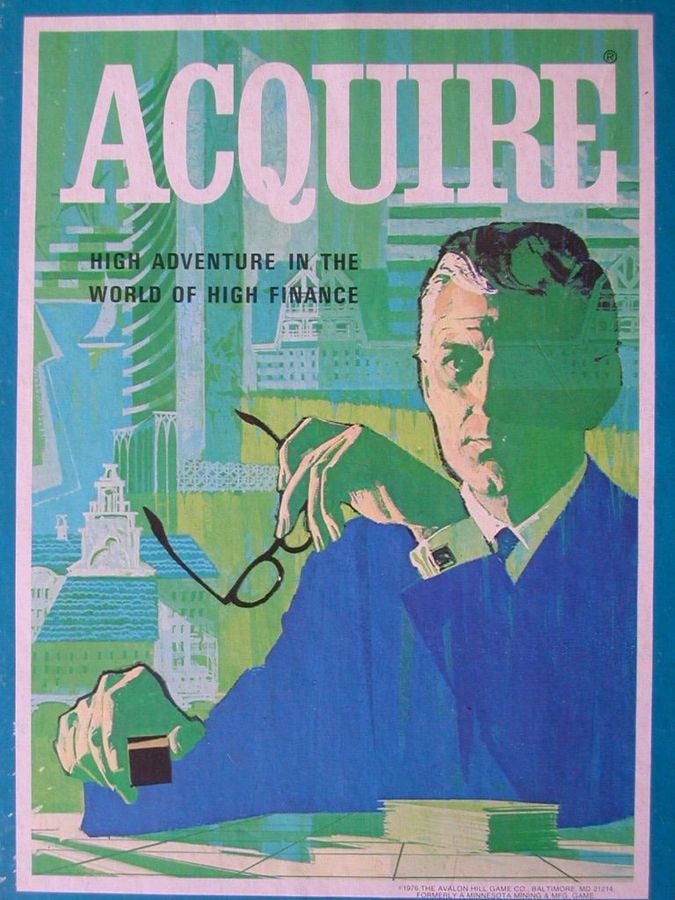

After a few more tries that didn’t work out, we hit on the idea of making it look like it had actually been published in the late 50’s, early 60’s. And a key touchstone of that era was the 3M series of games. I thought it could be very cool to have the cover look like a lost 3M game.

Bill rose to the challenge and produced these amazing images:

Those of you familiar with the 3M covers will see the resemblance immediately I am sure. Here’s Acquire, for example:

However, it still wasn’t quite right. It just didn’t grab us, and didn’t really seem to reflect the Vonnegut aesthetic.

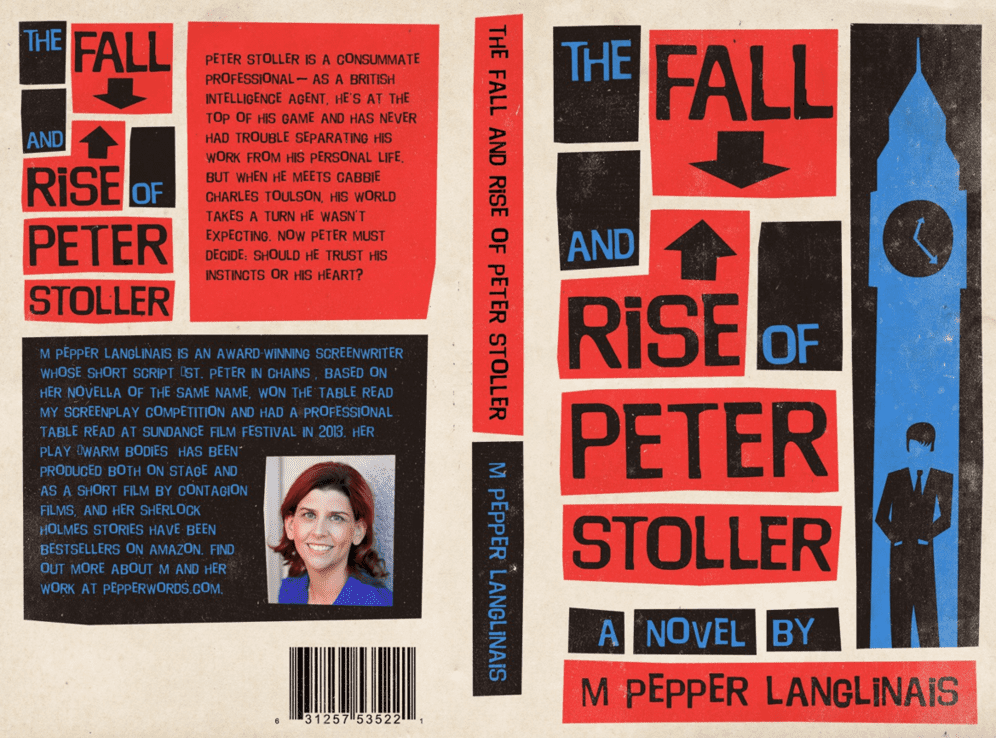

We reached out to some other artists to try to get some ideas, including Ian O’Toole. He sent back this book jacket in the style of a vintage 1960’s paperback as possible inspiration:

And it was like a light switch was flipped. This pop, pulp style said both 1960’s and Vonnegut. It really was perfect.

And, coincidentally, I was doing a new (still unannounced) game with WizKids, and the art was being done by Ryan Goldsberry, famous for his 1960’s-style illustrations for Burgle Bros and others. I realized he would be ideal for the cover.

And he delivered. Here is the final cover, which also features doodles in Vonnegut’s style, which just pull everything together.

If you’ve made it this far, I’m sure you can tell this has been a labor of love for everyone involved. And so all the details have been focused on making this as true to Vonnegut’s vision as possible.

During development the family actually found the original pieces in the attic and sent me photos.

We tried to keep the pieces as close as possible to these designs, while modifying them for playability.

We also included a 24 page history booklet that reproduces many of the original scanned notes for the game, along with placing it in the context of Kurt Vonnegut’s oeuvre.

As we received the first production samples of the game I received the following lovely note from Kurt Vonnegut’s oldest son Mark, who was eight years old when the game was being developed.

The success of Slaughter-House 5 and the other novels is nice enough but I truly believe he's watching somehow, someway, from somewhere and that the success of GHQ will be a greater and purely unadulterated pleasure.

Like a little kid with his brain, a jig saw and paint, he worked very long and very hard on the game which we played over and over trying to figure out what, if anything, was wrong with it. He was discouraged about his writing at the time, but had unshakable faith the GHQ would succeed.

I hope that you find this peek into Vonnegut’s life and creative process as fascinating and engaging as we did. Thanks to the Vonnegut family, Indiana University, Bill Bricker, and the team at Barnes & Noble for making this quixotic project possible.

As a writer, game designer, and lover of Vonnegut, this made me cry to hear this is being made. Will pick up a copy the moment I come across that beautiful box art in the wild. Thank you!

Thank you sharing the history of the project. Very, very impressive.