Let’s talk about colonoscopies and board games. (Insert joke about your least favorite game here getting a deluxe edition) This is real science. And sometimes science is not pretty.

Scientists were interested in learning about how we remember experiences. When we look back at something, how painful or pleasurable was it compared to other experiences?

In the 90s Don Redelmeier did a study at the University of Toronto. In this study, he worked with people undergoing colonoscopies. He asked them to record, at 60 second intervals, how much discomfort they were experiencing, on a scale from 1 to 10.

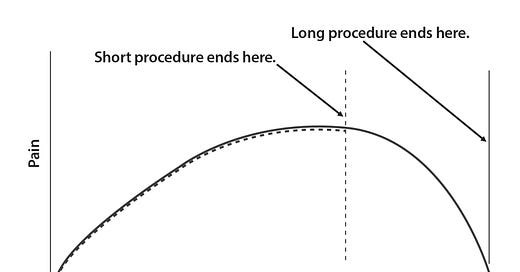

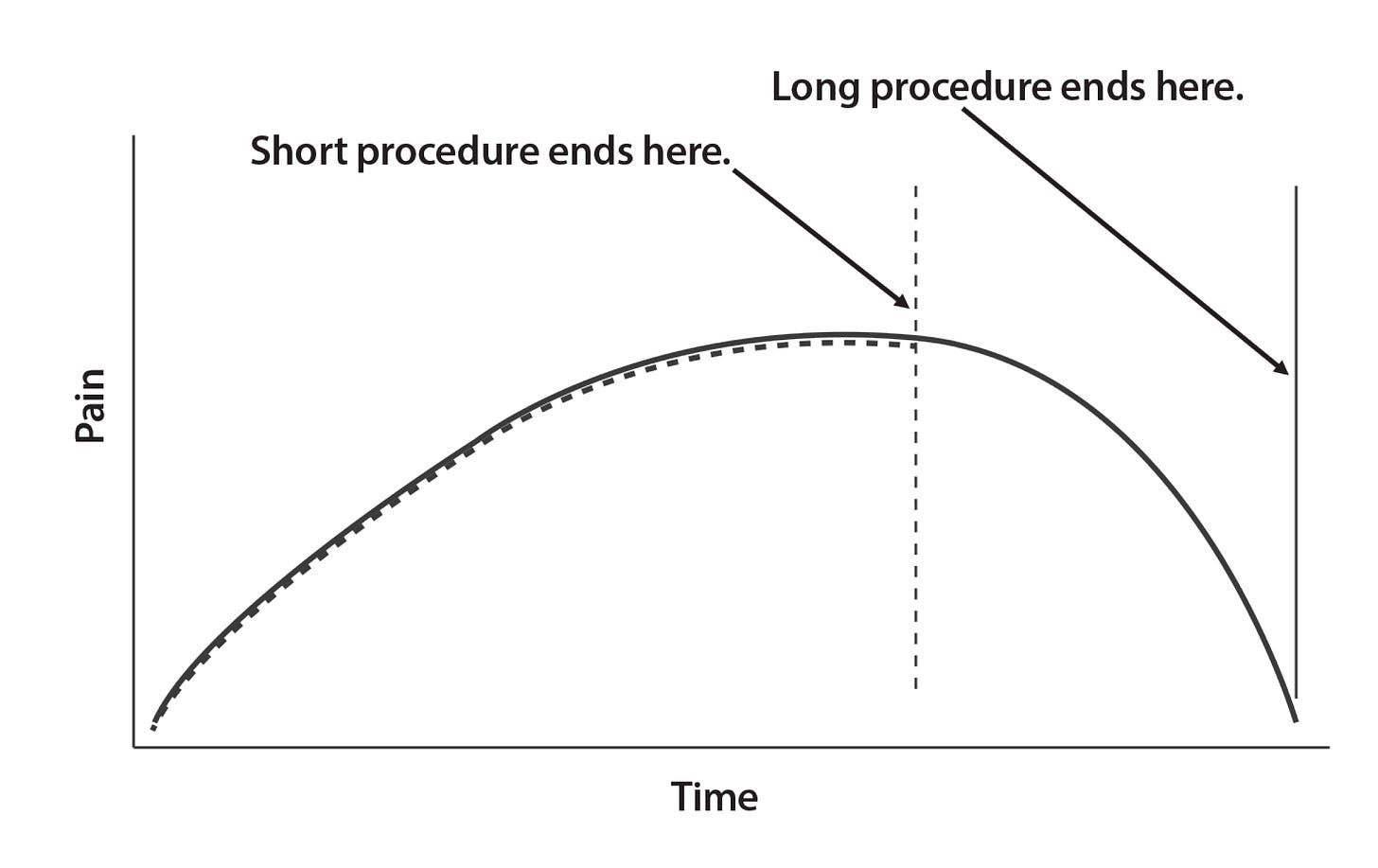

Let’s look at two representative patients – Patient A and Patient B. Patient A’s procedure lasts for 10 minutes. They record the worst pain at about an 8, and it happens close to the end of the procedure at the 9 minute mark.

Patient B also records the worst pain at the 9 minute mark, but their procedure lasts for 20 minutes, not 10. The first 10 minutes recorded by A and B are almost exactly the same, spiking up to 7 or 8. But B has an extra 10 minutes, during which they records the pain at around the 4 or 5 level.

So which would you rather be? It seems like Patient A gets the better deal here. Both A and B experience the same thing over the first 10 minutes, but then A is done. B has an extra 10 minutes before they are finished.

Well, after the procedure was over, the experimenter asked the patients to rate “the total amount of pain” they experienced. Patients that experienced procedures like Patient B reported much less total pain than Patient A.

As an aside, colonoscopies today almost always have zero discomfort. You should definitely get them as recommended by your doctor. Colonoscopies save lives. Don’t let these studies from 30 years ago dissuade you.

Psychology researchers prior to this always assumed that the “total pain” of an event would be the sum of all the individual pain recordings that people made during the procedure. This experiment, and many others done since, disprove this.

It turns out that people assign a “total pain” value based on the average of two things: the worst pain and the pain at the end. The duration of the pain has no effect on how we remember things. What happens at the peak and what happens at the end are the only things that matter. So Patient A, who had their worst pain right at the end of the procedure has a much worse memory than Patient B, who had less pain right at the end – even though it was twice as long.

So there are two “selves” that we have. The “experiencing self”, which is what we are actually going through at the time, and the “remembering self” which is how we remember events later.

This raises an interesting ethical question: Would you rather experience more pain but have a better memory of the event? Or experience less pain but remember it worse? This is not an idle question – it is something being explored today.

So I hear you asking, “Geoff, what does this have to do with boardgames?”

Well, it turns out that the same rules apply to things you enjoy – not just pain. The memory of an enjoyable event is based on the peak enjoyment, averaged with your enjoyment at the end. This is called the Peak-End Rule.

And this is why the end of a game is so critical. We’ve all had the experience of having a good time during the game, but then the end just falls flat. And we remember it as a “bad experience.” Or we play a game that’s not so exciting, but suddenly there’s a dramatic twist right at the end – and we remember it fondly. If that big twist happens in the middle, it is not nearly as memorable.

And looking at it logically, that really doesn’t make much sense. If you are enjoying yourself for two hours but are unhappy with ten minutes out of that, haven’t you had fun overall? Why does it matter if that not-as-exciting ten minutes happens during the middle or at the end? It shouldn’t. But it does. Our brains encapsulate events by looking just at the peak and at the end.

So game designers take note – endings matter. You knew that intuitively, but now you know it scientifically. People are truly their “remembering selves”, not their “experiencing selves”, and we need to design experiences with that in mind.

A Case Study - Space Cadets

Space Cadets is one of my earliest designs, co-designed with my children. It’s a cooperative game about being the bridge crew of a (non-copyright-infringing) starship.

Each player has one or more ‘stations’, like Shields or Weapons or Engineering, each of which has a mini-game that you need to do in 30 seconds to see what happens to the ship.

The main game worked well and playtesters had a great time during the missions. But while sometimes there were great stand-up moments at the end of the game, often the end just… happened.

One way the mission ended was if the ship was destroyed (a loss, obviously). The damage system was clever - there was a schematic of the ship, and depending on what side you got hit on you removed tokens from that area, which sometimes did nothing, and sometimes damaged systems. At the center of the schematic was the core. If that got hit, it was game over.

It worked, but it was anticlimactic. Aliens would shoot at you, you’d roll some dice, and you just… blew up.

Winning, depending on the mission, also could feel anticlimactic.

So we huddled and came up with two systems that created memorable moments on both the winning and losing ends of missions.

To win the game, we added a new condition that the players needed to successfully jump out of the system. For this we added a Yahtzee-style dice game, where you had to roll five of a kind to succeed. During the game you could ‘prime’ the jump engines, and earn cards that let you manipulate the dice.

This did two nice things. First, it gave players a tough choice during missions - should they spend valuable energy trying to earn jump bonuses to make it easier to jump out at the end of the mission? Or just focus on the goals and deal with it later?

Second, to Jump you only have 30 seconds to get all the dice to five-of-a-kind. While one player is the Jump Officer and actually manipulates the dice, everyone can watch and make suggestions and yell and cheer. And when you do jump, it’s a really exciting moment, with everyone screaming.

On the losing side, we added a new minigame called Core Breach. We got rid of the fiddly token system for just stacks of cards on each side of the sip. If a stack ran out of cards another hit there caused a ‘core breach’. This didn’t end the game. But if you didnt’ repair the core during the next turn the ship would blow up and you’d lose.

If a Core Breach occurs, during the next turn you take a certain number of Core Breach cards (the greenish cards on the right side above), and pass them out to the players. The first time there’s a Core Breach you pass out three. Each subsequent Core Breach makes the number go up by one.

During the next 30 second Action phase, one player starts with a deck of Core Repair cards. They need to find the card with the matching shape on their card, then pass the deck to the next player. If players find all the matches in 30 seconds they repair the breach and life goes on as normal. If not, the ship explodes.

Plus players do this while doing their regular jobs in those 30 seconds (loading torpedoes, navigating, etc). So it naturally degrades the normal functioning of the ship.

I'm really proud of the Core Breach mechanic (the idea was from my son Brian). It completely did what we wanted. It’s incredibly thematic, and when you lose the game, it still is a climactic moment, with all players involved. And you think you could’ve done it successfully if you had another shot - the game didn’t just hose you randomly.

This psychology is helped by the first level - three cards - being really easy. It’s almost impossible to fail at this level. But by the time it gets up to six or seven it becomes very challenging. However, since the deck gets thinner as it passes around the table, each subsequent match goes faster, and there’s a feeling of acceleration, even at higher breach levels. It always feels do-able.

When we first tested these changes, the impact was immediate and obvious. Even when teams lost, they lost in an exciting and engaging manner, which made all the difference.

Space Cadets is not without its faults - the biggest being that we radically underappreciated how tough it would be to teach players a bunch of different minigames, even if all are very simple.

However, by embracing the Peak-End rule, and specifically designing in incredibly exciting endings, both on the winning and losing side, people have fond memories of the experience.

Go out with a bang and not a whimper.

good advice as always Geoff