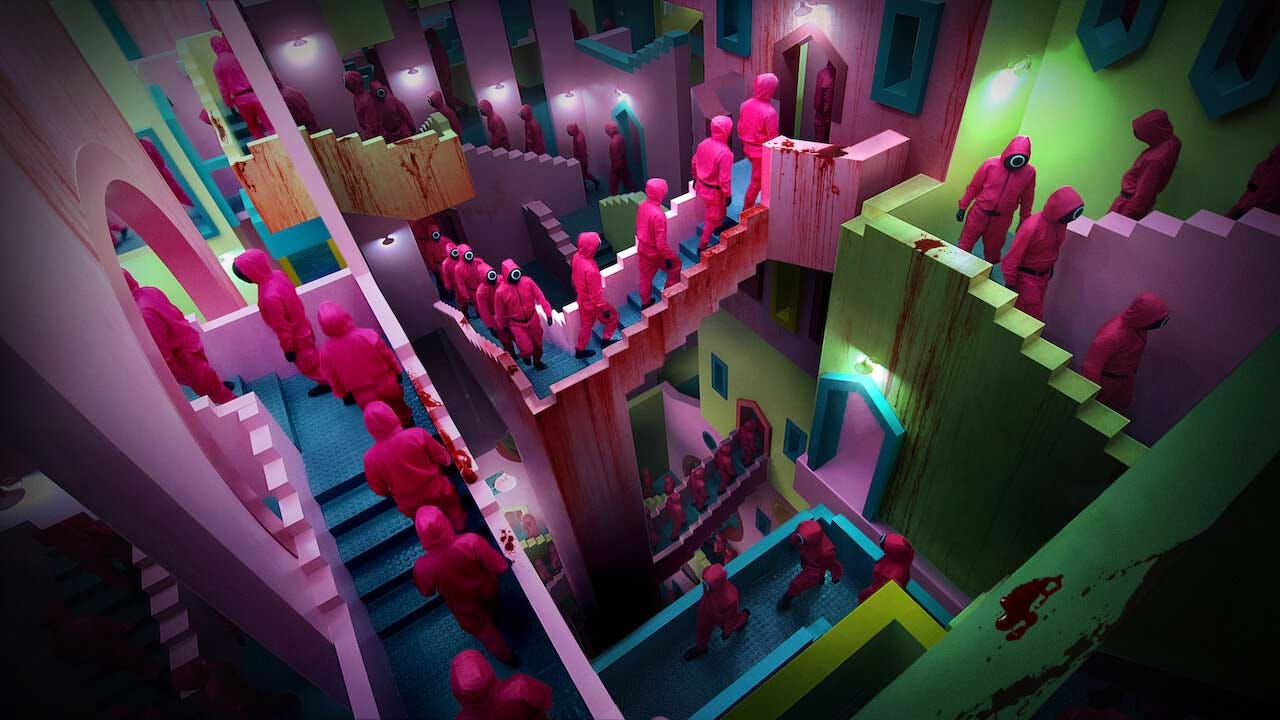

The South Korean drama Squid Game was one of the most watched shows on Netflix in the United States. It is centered around a series of games for the contestants, and their design, while simple, illuminates several principles of game design.

There is also a lot of social, political, and class commentary, which is worth thinking about and exploring. But I won't be doing that here.

On to the games. But first… FINAL REMINDER: Massive spoilers below!

OK - still here? Let's get started.

Player Experience

When I talk to people about game design, a question I am frequently asked is "do you start with a theme, or a mechanic". My standard reply is neither - I start with the player experience. How will the players feel while they are playing the game? What is their emotional state? What stories will they tell about the game afterwards?

Now in one sense this is a bit glib. I don't sit down and say "I really want players to feel jealousy. Let's design a game that does that!". The experience arises out of the setting, who the players are, and so on. For example, the genesis of the idea of Space Cadets was creating the comradery, tension, and excitement of being on the bridge of a giant starship. For Versailles 1919 it was making decisions that remade the political geography of the world while satisfying your constituents back at home.

Many would consider this designing to "theme", and in a sense they are correct. But I do think that "experience" goes beyond theme. "Zombies" are a theme, but there are many different experiences that fit into that theme:

An individual trying to survive in a mall until help arrives

Leading a band of survivors establishing and defending a camp

Leading a nation attempting to win a war against a zombie invasion.

All of these are thematically Zombie games, but bring very different experiences with them. And all have been successful, but very different, board games.

Squid Game is actually a rarity in that the games are specifically designed around the emotional core, without any thematic elements. And that emotional core is anxiety, and the related fear and interpersonal conflict.

Many elements of the games combine to create anxiety in the players. The most obvious are the stakes. The players are, quite literally, playing for their lives. That naturally will increase the tension for the players, and perhaps also their focus and attention (making a mental note here for future game designs...)

But more impactful than the threat of imminent death is, in my opinion, uncertainty. Just about every game is designed to create keep key information from the players, mostly in the form of having to make decision prior to knowing what the game is. Ppogi (the sugar candies), Tug of War, Marbles, and the Glass Bridge - all require players to make critical decisions, like who to team up with, or what number to select, before the game starts, under very incomplete information.

There are also rules within the games that are not clearly laid out. In Marbles, what happens to players that aren't chosen for a team isn't specified. Neither is what happens if neither player in a pair wins the game - an omission that Sang-Woo uses against Ali. Similarly, the pretty important fact that losers will be killed is conveniently omitted from the explanation, to be introduced later with devastating impact.

Even other elements in their lives during the game - small meals, being locked in at night, specific bathroom times - are designed to put the players more at edge and against each other.

Only the final Squid Game is clearly understood by both players. But by that time the game is down to two players, and the design goal of creating interpersonal conflict no longer applies. As the desired experience changes, the game design changes as well.

Competence

The introduction of uncertainty through most of the games feeds into a psychological concept called competence. In this clinical sense, competence is expressed as a ratio or percentage, and is roughly the amount you know about a situation divided by the total amount there is to know.

People prefer situations where they have higher competence.

Here's an example to illustrate this point:

I propose we play a game.

You pick evens or odds. Then you roll a six-sided die, and if you're right, you win.

Here's another game:

I secretly roll a die and put it under a cup. Then you pick evens or odds. I lift the cup, and if you're right you win.

Which would you rather play? About 2/3 of people surveyed prefer #1. Mathematically they are both the same, but psychologically we feel more at ease with the first.

The reason goes back to competence. In the first game, where you make your choice and then roll the die, when you select even/odds you know everything there is to know about that situation. There is no hidden information at that moment.

In the second case, there's a big fact you don't know - what the already-rolled die actually is. It is a fact that now exists in the world that you don't have access to.

From a psychology standpoint, making decisions under low competence creates anxiety and discomfort.

I was recently playtesting a game for someone, and it was roughly in two parts. In the first part the players drafted cards, and the second part they used those cards to fight a battle. Some of the cards must have been better than others, as the amount you had to pay for them was different - it wasn't just a pick and place draft. But the cards all came in different varieties - units, weapons, special events, supply, and others.

We were not playing with the designer, and were completely adrift during this initial part. Do you need a mix of card types? What were some combos to try to obtain? Unfortunately, the second half of the game was complex enough that even though we read through the rules it wasn't clear how things were really going to play out. So we ended up selecting on gut feel, but it was very much a low-competency situation, and one we did not enjoy. I'm sure it would be completely different the second playthrough, when we understood the game, but given the first play no one was interested in trying again.

It's critically important to give your players signposts early on, to give them quick short term goals, to get into the flow of the game. In this game, if the designer wanted to keep this structure, they needed to include guidelines about what cards make up a reasonable deck, or perhaps just have premade decks for your first playthrough.

Competence can be leveraged in subtle ways to manipulate player experience. We talked earlier about rolling a die. Often that die roll can instead be a card flip. Competence makes flipping the top card of a deck feel fundamentally different than rolling a die, even if functionally they are the same. With the card deck, your fate is already known to the universe at large, even if it is hidden from you.

If you're interested in exploring this idea of Competence more, I discuss it at length in my book Achievement Relocked

Who is the Player?

I was actually cheating a little bit earlier, talking about the player experience. In Squid Game, who we think are the players are not actually the players. The game is designed for the people wagering on the outcomes - not the people playing the game. So the designers are motivated to create situations that will be interesting to observe for those outside the game - not really the players themselves. Although the games are positioned as 'fair' and a way for the underclass to rise above their situation, it is not actually for that purpose. It is to create a spectacle that people will pay to see.

While most often we design games for the players, there is still a lesson to be learned here. If you want your activity to be a spectator sport, it needs to be designed to appeal to the spectators, not the players. Baseball is currently going through a spectator crisis of sorts, as the games are slower and longer. The end of basketball games, with their endless parade of fouls, drives away viewers and breaks the flow of the game. The players don't necessarily care about either of these issues - they are concerned about winning, and adopt strategies that will lead to that. But the spectators - who are paying those salaries, after all - care a lot. They want to be entertained.

Even if there are no spectators, as a designer you need to make sure that the winning strategies are also fun to play. If the best strategy is holing up in a clump and doing nothing (I'm looking at you, Abalone), that's no fun for anyone.

The Magic Circle

When we sit down to play a game, we adopt what is called a 'ludic mindset'. We all agree to abide by the rules of the game, and enter a sacred space, a separated world, where those rules are in effect. This concept is called The Magic Circle. It was first introduced by Johan Huizinga in Homo Ludens, published in 1938, and expanded and popularized in the 2003 Rules of Play, from Katie Salen Tekinbas and Eric Zimmerman.

At the start of the Squid Game, the players are made to sign a contract that contains the 'rules'. By doing so they enter into the Magic Circle.

However, the Magic Circle, extends beyond the simple rules of the game. It encompasses a whole range of behaviors, like you will actually take your turn in a timely manner, or even at all. There are very few games that specify that you must take your turn within a certain amount of time. But violating that unwritten rule will break the magic circle.

Similarly, intergroup behavior is a part of the magic circle, and different groups may have wildly different approaches to this. Some groups may gleefully embrace trash-talking, while in others, that is frowned upon.

Earlier I talked about how in Red Light, Green Light, the players are not told that losing players will be shot - a rules omission that I'm sure my family would expect me to make given my track record with teaching games.

This goes beyond the expectation of the Magic Circle, and panic ensues. When the players return after the first game, they do so voluntarily, and with an expanded understanding of the Squid Game's magic circle. Death is now expected.

However, the magic circle is not done being expanded. After the second game, gangster Deok-Su kills another contestant in the barracks, creating one of my favorite moments. Everyone stops, and waits to see what the folks in charge will do. There's an extended moment of silence, and then the player count drops by one and additional money is added to the piggy bank. Killing contestants directly has just been added to the magic circle.

I - and I'm sure every parent reading this - has seen that moment with kids. They do something, freeze, and then look to their parents to see if there will be any consequences. These moments are critical, and are such a clear branching path.

The players have now witnessed hundreds of deaths. But this one killing still stops them in their tracks, because it was outside the magic circle. This type of killing - player on player - is still taboo.

Because it is now allowed, the players re-evaluate everything. Alliances and plans are hastily set up for the night. It even retcons some of the earlier games. Could players have run around during the honeycomb game and broken other players' candy? Maybe. It certainly opens up a whole raft of new strategies and tactics.

And that night mayhem breaks loose as players try to eliminate the competition. Now that players know they can kill with impunity as a path to victory, many of them do so.

Dark Magic

Players killing other players in Squid Game demonstrates the dark side of the magic circle. Most of those people would not directly kill in the outside world. Because there is a special set of rules within the game, those rules can dictate behavior counter to what we would normally do.

Ordinarily this is benign, like not being to talk in Hanabi, or holding your cards backwards. However, it can be used for a darker purpose. Cults can create warped rules for members that can lead to self-harm.

One example of this in board games is Cards Against Humanity. A big part of the appeal of CAH is that it specifically has rules to create a magic circle that 'forces' players to do things they would not do in 'real life'. The rules say the judge has to read the cards out loud. So you can make someone say something they never ever would - or perhaps even worse (and more realistically), you are giving yourself license to say things out loud that you would not. The magic circle gives you a get-out-of-jail-free card. After all, you don't want to say those things. But the rules say you have to read what's on the card out loud, and that's what it says on the card, right? I'm just following the rules.

Shut Up and Sit Down had a fantastic article about this. I highly recommend giving it a read:

Review: Cards Against Humanity - Shut Up & Sit Down (

Squid Game shows this on a number of levels. The players do things they would never normally do because they are sanctioned by the game. I don't think it's strictly a "Lord of the Flies" situation where people devolve when removed from civilization. The players have pledged themselves to specific rules of behavior, not just chaos. And they are 'simply' following those rules.

And the guards and other people that work there also go along with all of the rules they have agreed to. They are in a magic circle of their own.

As designers, creating and maintaining a positive magic circle comes in many forms, most of them falling under the umbrella of 'immersion'. If players lose 'immersion' they may find themselves on the outside of the magic circle looking in. Actions that were imbued with meaning within the context of the theme and experience become mechanical and hollow.

The Bridge Game

Relating to the magic circle, I'd like to take a closer look at one game in particular - the Glass Bridge. As a refresher, in this game the players need to cross a bridge. Each step there is a left and right glass pane, and players need to select one. One of the panes is tempered glass that can hold them, and the other will collapse, causing them to fall to their deaths. There are 18 steps, so the first player going has a 1 in 2-to-the-18th power chance of succeeding (1 in 262,144 for those at home) - not so great. But each player after them has an increasing chance, as panels get broken and the correct path is found.

Before the players know what the game is they need to pick bib numbers, which turn out to be the order they must cross the bridge. This is a great example of what we talked about earlier - making choices when you have no idea what the implications of your choice are.

Our hero, fortunately, chooses the highest number and gets to go last.

The players head out across the bridge, with those in front crashing through and showing the correct path to those behind, who are strung out like beads on the earlier safe panes. But then the player in ahead of our aforementioned gangster Deo-Su crashes through a pane, and it is now up to him to make the next move.

But he chooses to simply not move at all. He would rather they all die when time runs out rather than move forward and die alone - while also helping out the group by showing the correct path.

This is a great example of behavior in a semi-cooperative game. For those unfamiliar with the term, a semi-cooperative game is one where there are usually one or more winners, but if the players don't cooperate to a certain level there is a chance the game will win and all the players will lose.

A classic example of this is the zombie game Dead of Winter. In Dead of Winter, each player is a survivor in a camp trying to fend off a horde of zombies, while also fulfilling their personal goals. If the players fend off the zombies, whomever fulfills their personal goal wins the game. But if the zombies overrun the camp everyone loses.

Semi-cooperative games, more than most, require all the players to be on the same page about how they are going to play the game - in the same magic circle, if you will.

The designers intend the three victory conditions to be ranked by players like this:

Best: I win

OK: Someone else wins

Worst: Zombies win

However, this isn't the only way to rank these. Some players instead will consider their preferred outcome ranking to be:

Best: I win

OK: Zombies win

Worst: Someone else wins

Thematically perhaps this doesn't make sense. But it does game-wise. The second can be understood as:

Best: Win

OK: Tie

Worst: Someone else wins

...if you equate 'everyone losing' with a tie, which is not unreasonable.

Deok Su is applying the other ranking. I would rather everyone lose than just I lose. Is it selfish? Maybe. But why should he take a very slim chance of survival just so that people he is competing against have a much better chance of winning? He's the bad guy in the show, but I think he may have a bit of a point here.

I find semi-coops devilishly difficult to get right as a designer. You have to work very hard to ensure that players are all on the same page - usually through theming. However allowing players to threaten to 'tank' the game is an important element to have in the game. Part of the charm of semi-coops is that you can't be too mean to someone and kick them to the curb - otherwise they will feel justified in dragging you and everyone else down with them.

And that's how Deok-Su feels at this moment.

As a designer you can't just take out the 'I'm gonna tank this game' option, otherwise there's no reason for it to be a semi-coop. But that needs to be an extreme choice for the players - not a threat to be made lightly. Again, a hard needle to thread.

Subversion

One last thing game designers can learn from Squid Game: Players will always - always - try to subvert your game. You didn't realize one of the players manufactured glass for years and can tell the difference between normal and tempered glass? Sorry! Your fault! Even when life and death are not on the line, players will look for every edge they can to break your game and short-circuit your carefully crafted machine.

Seong Gi-Hun subverts the final game when he refuses to win and invites Sang-Woo to join him in voting to end it - forfeiting their prize and actually giving the prize money to the deceased contestants. This works counter to the point of the game the designers have set up, to make it appeal to the higher-level players placing wagers. If the games conclude unsatisfactorily, from the perspective of the VIPs, who presumably are paying for everything, it will tarnish the Squid Game brand and possibly prevent them from being played again, as the VIPs lose interest. Sadly Sang-Woo chooses to take his own life, perhaps wracked by guilt at the end, and ironically ensures the game will continue in the future.

I hope you enjoyed this deep dive into Squid Game. Drop a note in the comments to let me know what you thought, and if there are other design lessons to be learned!

Expanding on your final point, I suppose you could look at the players' forfeiture of the prize money as them losing interest in the victory points. Without going into the commentary you wanted to avoid, I think there's a very interesting consideration of the vast difference between games that do and do not feature monetary rewards. There's an inherent "meta" circle that exists when playing for money in that you're playing for a resource that will presumably continue to help you in the real world (i.e. outside the game and its magic circle). Not only does the game's magic circle have a direct, unbreakable and constant connection to the outside world (that, I would argue, prevents the magic circle from fully forming a solid boundary), but it also affects the players' experience: the amount of victory points (money) matters, and it matters a different amount to different people. This might be comparable to something like a legacy game where you keep some resource reward from game to game, but obviously it goes beyond that.

Casino type games are the obvious example of this phenomenon, but it also has me wondering about traditional games that gain such a competitive following that there becomes an economic basis to allow for rewards. Chess comes to mind as a game that is treated like a sport at a high level in this way. It just has me wondering now about how "external" incentive changes the player psychology and perception of the game, how does it change the experience. Does it automatically break or weaken the magic circle if you're playing at the World Series of Boardgames, for example? Thoughts?

Thanks again for these emails. I really have all my designs on the backburner, but they are making me think of dusting them off.

A few points.

The people running the games in Squid Game were pretty steadfast in keeping the games "fair" so I doubt they would have allowed cookie breakage.

Deok-Su was also breaking the game for a more obvious reason. He knew that the others would eventually do his bidding by sitting and waiting since they didn't want to lose their lives. He leveraged a position that he knew he had, just like many in semi co-ops.

I hate semi co-ops under their current premise. I "tanked" a game because I knew I wasn't going to win under the same premise. I think they are failed designs because of that.

I think there is a better way to do semi co-ops by using those elements in different places besides the winning condition. I have a game on my backburner where there are scoring elements that are handed out when a threshold is met that are BIG points... but they are only handed out to those that contribute to that element's threshold being met. You help to overcome the big monster, you get credit... if you were instead doing something else with your actions, no pie for you. A person in that game is very unable to win if they ignore EVERY monster that comes to play because the points are too big, but they might win if they engage 1 or 2. If everyone ignores the monster, bad things happen to motivate them.

It may not be the cleanest solution to the goal, but I like that way better than playing 2 hours to have someone tank and make a "meh" or "never again" experience.