Game, Set, Match

Tennis is structured as a series of sets (best of 5 sets for men, best of 3 sets for women), with the first player winning six games winning the set (assuming they win by two. If it gets to 6-6 there is a tiebreak played). And each game is played to 4 points (0=love, 1=15, 2=30, 3=40, 4=game - don’t ask), and again you need to win by two.

Is this fair? Does the better player win?

A recent paper says no. Well, not always.

Making tennis fairer: The grand tiebreak is from Brams, Kilgour, and Seven. They specifically look at matches where one player wins more games than another player, but loses the match.

For example, the set scores may be 1-6, 6-4, 6-4. The losing player has won 14 games (6, 4, and 4), and the winning player 13 (1, 6, 6).

The paper authors believe that this is eminently unfair, and propose a remedy - The Grand Tie Break.

Basically, if the winner of the most matches is not the player who won the most games, there would be a special tie break, which would be conducted the same way as a normal set tiebreaker (first player to seven points, must win by two).

Other than perhaps being “fairer” (debatable), the authors say that this will have the positive effect of making every game count that much more. Even if a player is far behind in a set they have incentive to try to win as many games as they can to avoid the Grand Tiebreak.

A Swing and a Miss?

Personally, I am not a fan of this proposal (as you might guess). It just generally makes everything more math-y without really adding much more excitement. A dominant comeback performance in a final set can be just as exciting as needing a ‘Grand Tiebreak’ mechanic. Although I did appreciate the extension Markov-Chain analysis of a tennis match. But maybe that’s just me.

But - why stop at Games? Why not look at how many Points each player scored? What’s privileged about Games? The authors don’t discuss this.

Finally, other sports have this ‘issue’, but the authors don’t address that at all. They act as if tennis is the only sport that faces this.

But any sport or game that ‘clumps’ points into a single victory or defeat will have this issue.

For example, let’s take a look at the sport of baseball. In the World Series, the team that lost the series scored more runs than the winner a bunch of times - most recently in 2025. The losing Toronto Blue Jays scored 34 runs, while the victorious LA Dodgers scored just 26.

That is primarily due to the first game, which the Blue Jays won 11-4. And generally the Blue Jays won their three games by big margins, while the Dodgers just squeaked out wins.

In the 1960 World Series, the Yankees scored 55 runs, more than double the 27 scored by the Pirates. But the Pirates won 4-3.

Can you imagine that if at the end of the World Series or the NBA championships that if the losing team outscored the winning over the whole series they had to play a special tie break? It just wouldn’t feel right. It would also create other weird effects as teams know then need to win by a certain amount to avoid it.

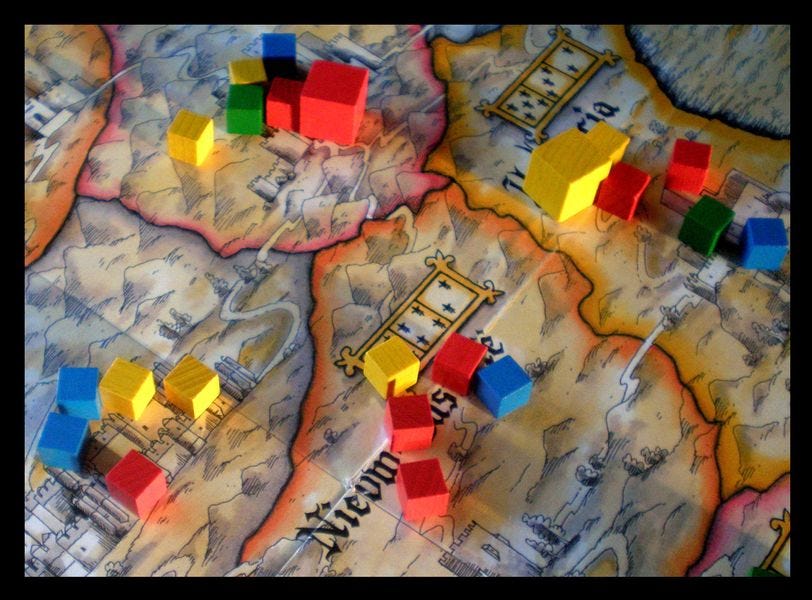

Area Control Games

This feature of “chunking” plays a key role in many games, but particularly in Area Control games like El Grande and Smash Up. (Have you played El Grande? You should play El Grande.) A key ‘experience’ that these games create is efficiency - which doesn’t sound that exciting but absolutely can be. You have limited resources and need to figure out how to deploy those to maximum effect. If you win a province by 8-1 that’s really bad. Yeah, it’s secure and dominant, but meanwhile your opponents are winning other territories by 3-2 and 4-3.

Some of the key considerations that you as a designer can use in area control games are:

How do resources enter territories?

How do they leave? Can they be transferred?

How do you deal with turn order? Going last in an area control game can be critical.

How do you vary the value of the regions / rewards?

How do you add uncertainty to resolution (and do you want that)?

When playing an area control game, pay attention to how the designer dealt with these questions to craft an engaging experience.

War Games

War games are also about effectively allocating your resources. Sometimes you want to have a local super-majority, so you can get a breakthrough, while still holding the rest of the line. Shifting resources around to exploit enemy weak points is another example of ‘chunking’, as is the old wargame concept of ‘soaking attacks’.

Soaking attacks were common in older Avalon Hill wargames. If you were next to an enemy unit you needed to attack, so if you just matched up a line of tokens against each other, it was hard to get an advantage. Instead you would concentrate your stronger units at a single point to get a high odds attack, and sacrifice a lower strength unit to ‘soak’ against one or more strong enemy units at very bad odds. That way you can create gaps and eliminate strong enemy units in exchange for weaker ones of your own.

This was an emergent tactic, by the way. There was never an explicit rule that explained that you could do that. Players just figured it out.

I also used the idea of efficiency (in a less-obvious way) in my game The Fog of War. In that game, players secretly prepare offensive and defensive operations. When you reveal the forces, ideally you want to win by as little as possible. New players tend to overcommit to key operations to make sure they win, rather than use intel and do a better job optimizing the use of their forces. In the early stages of the game, which is about WW2 in Europe, the Allies can’t stop the Germans everywhere. They need to bluff the Axis into overcommitting into some areas, winning by a lot, while the Allies muster their forces to win a few battles here or there and throw off the German timetable.

Auction Games

The Fog of War mechanism is reminiscent of a Sealed Bid Auction, where players simultaneous make secret bids and reveal them. Winning can be disastrous if you win by too much and overcommit. You can end up behind the curve for the rest of the game.

Even if there isn’t a sealed bid, understanding the options your opponents have and planning accordingly can be a key tactic. The bidding tiles in Ra are a great example of this. Your opponents’ options are known but figuring out how to force (or at least entice) them into using their tiles inefficiently can be very satisfying.

Other Chunk Sightings

‘Chunking’ can be seen in lots of other places. One to highlight is end game scoring. Often a game will award a fixed bonus to a player that has the most of a certain resource. This presents a challenge to a player in terms of how much to chase after that, and how much of a buffer to give yourself to deter rivals.

Trick Taking games can also be viewed as a form of chunking. If you win a trick with an trump ace or a non-trump 6, it still counts as one trick. You want to win as efficiently as possible.

Gerrymandering

There’s one hot-button issue that this idea of Games vs Sets directly relates to - Gerrymandering, the political math of dividing up voting districts to give an advantage to one party.

This is a whole other topic that is actually mathematically fascinating, while having major real-world implications. I do plan to do a future GameTek on gerrymandering, but I think this column is running long already. So soon!

So what types of chunking have you seen in games, and how well do they work? And what are your thoughts on the tennis proposal that started this all? Let me know in the comments!

I'm in full agreement on the tennis proposal. Totally unnecessary and makes the game more complicated without really adding anything.

The most obvious game that jumps to mind regarding resource efficiency is one where you have no control over that efficiency: War. Taking a 2 with your Ace is a disappointment, even though you 'won' the exchange. You want to be getting a King with that Ace! If nothing else, War can at least be instructive to young kids about resource efficiency in games.

Oh, here's another one from a game I pulled out just this past weekend: in Space Cadets, the Tractor Beam station wants to try to be as efficient as possible with their tiles. If they burn pairs of 3s and 4s when they don't need them, they might run into real trouble later on when all they have left are 1s and 2s.

Brilliant framework for understanding efficiency in games. The chunking lens really clarifies why area control games create such satisfying tension - its not just about winning territories, but the constant calculus of when to accept losses vs overcommit. I've noticed this same dynamic in deckbuilders too, where buying a slightly weeker card to preserve economy often beats chasing the perfect purchase.