Great Expectations

Mathematical modeling for game design

One of the questions I frequently see about tabletop game design is how much designers should use mathematical modeling to analyze their designs.

My stock answer is that playtesting will give you just as much information about balance and costing as modeling. But modeling will get you to an answer faster.

Part of the issue is that building a full model of most games, and developing algorithms to walk through potential strategies can take a long time - and if you make a mistake somewhere along the line (more likely as the simulation gets more complex) the results can be counterproductive, giving you false assurances.

Having said that, understanding the math behind your design choices is very useful and often vital.

There are many formulas and techniques to assist in this. Two examples that I have covered already here on GameTek are the Hypergeometric and Binomial distributions, and Markov Chains.

I’d like to talk about a third concept - Expectation Value - and how me and my kids used that in our latest release DC Breakout.

Defining Expectation Value

If you roll a die or draw a card or time how long it takes you to drive to work, you will get a range of values. It’s not the same thing over and over again.

Expectation Value (EV) is the average of what you can expect over the long term, if you repeat the same activity over and over. It does not predict what a specific die roll will be, but it does tell you what the expected outcome is.

The expectation value is calculated through this formula:

EV = (p1)(v1) + (p2)(v2) + (p3)(v3) + …

where p1, p2, etc is the probability of result 1 occurring, result 2 occurring, etc, and v1, v2, etc are the value of the outcome.

Let’s take a simple example - rolling a standard D6.

There is an equal chance of rolling each side: a probability of 1/6.

The value is just the number on the side.

So the EV is (1/6)*1 + (1/6)*2 + (1/6)*3+ (1/6)*4+ (1/6)*5+ (1/6)*6

which if you run through all the math is 3.5. In this case it’s the average of the die faces, since the chances of each coming up are equal.

Dealing with fractions can often be a pain, so another way to calculate it is to multiply by the number of ways a certain result can be achieved, instead of the probability, and then after adding all those up to divide by the total number of ways:

EV = ((n1)(v1) + (n2)(v2) + (n3)(v3) + …) / (Ntotal)

n1 is the number of ways you can get value v1, and so on.

Ntotal is n1 + n2 + n3 + …

So for our die example, the expectation value is expressed as:

EV = (1*1 + 1*2 + 1*3 + 1*4 + 1*5 + 1*6) / 6

which is also 3.5.

This example is pretty simple, and it’s obvious that on average you would roll a 3.5 on a D6. So let’s look at some real world examples.

Killer Croc

In DC Breakout you play a pair of villains escaping from Arkham. Your turn is simple - roll a die and move that number of spaces. First pair to the end of the track wins the Escape.

Each villain, of course, has their own special power. And part of the fun is figuring out which two villains of the ones you are dealt will work well together.

When designing DC Breakout, we used EV calculations extensively to help us balance the powers. Let’s take a look at a few, starting with Killer Croc:

His ability is straightforward: Any even roll is changed to a 6.

What is the expected value of this ability?

Well, the six possible die results are 1, 6, 3, 6, 5, 6, since two and four get turned into a six.

There is one way to get a result of 1, 3, or 5, and three ways to get a result of 6:

EV = (1 + 3 + 5 + 3*6) / 6

EV = (27 / 6) = 4.5

So on average Killer Croc will move 4.5 spaces per turn. This is exactly the same EV as getting a +1 modifier on your die roll.

Could we have made Killer Croc’s ability simply to gain a +1 on your die roll? Sure. But there are a few other considerations:

The ‘change even numbers to sixes’ sounds more exciting than a +1 modifier. The brain says - Wow! That’s huge if I roll a 2!.

It interacts and combos differently with other abilities. More on that later on.

But simply being able to quickly understand that this ability was the same as a +1 made it easy to think about in comparison with other abilities.

Bane

Let’s take a look at Bane:

There are two parts to this ability. First, you roll two dice and then you select which to use.

For purposes of our first analysis, let’s assume you always pick the highest. This is equivalent to ‘rolling with advantage’ in Dungeons & Dragons and other RPGs.

The results of this procedure will still be from one to six. But to calculate the EV we need to know how many ways it is possible to roll each value.

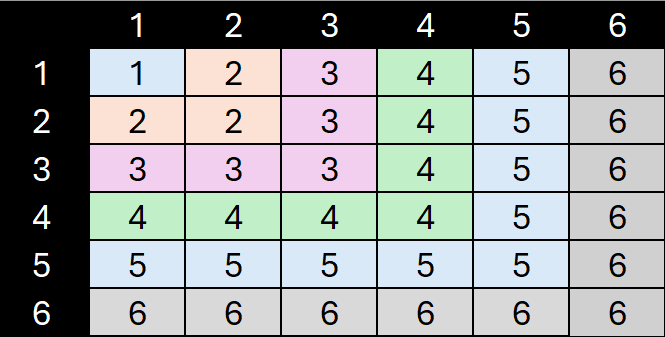

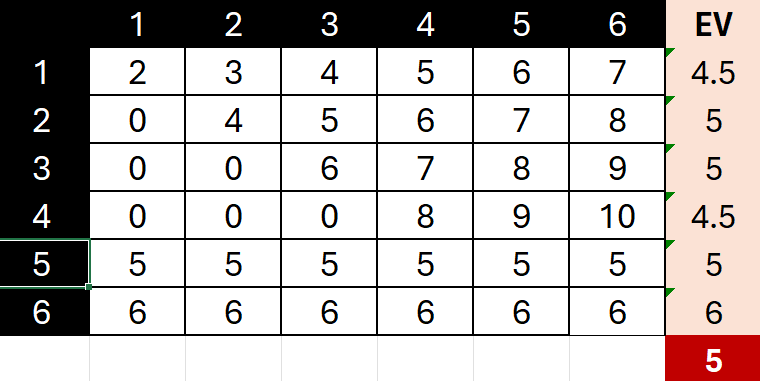

For this, let’s make a 6x6 table showing the possible outcomes:

If I roll a 4 and a 3 (or a 3 and a 4), the result will be 4.

From this table, we see that there’s one way to get ‘1’, three ways to get ‘2’, five to get ‘3’, and so on, up to a whopping 11 ways to get ‘6’. So:

EV = (1*1 + 3*2 + 5*3 + 7*4 + 9*5 + 11* 6) / 36

We divide by 36 because that’s the total number of ways to roll two dice (and also the sum of 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 + 11).

If you work through the math, you’ll see that the EV is 169 / 36, which is just about 4.7.

This is slightly above Killer Croc’s EV of 4.5. So again we have come up with a fancier way to give a character +1, although again this character synergizes different than Killer Croc - both because of the die roll distribution but also because Bane can choose the lower die, which can be advantageous sometimes.

Falcone

Let’s look at one last Villain ability - Falcone:

This is a slightly more complex ability, as it requires a choice from the player. Do you gamble with the second roll or not?

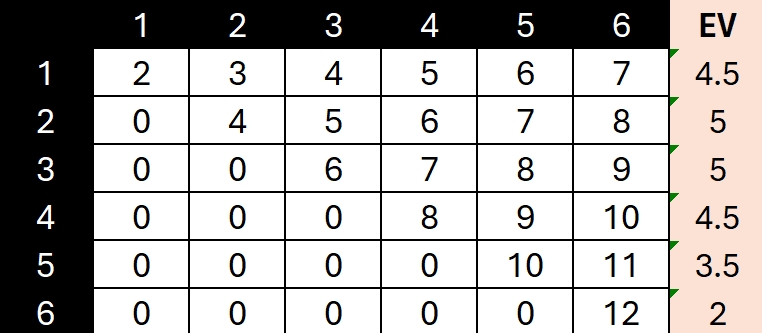

For the EV calculation on this character we approach it in two stages. First, we will break down the EV for each of the six possible first rolls.

For this we will assume that we ALWAYS roll the second die.

Let’s start simple - assume the first roll is a ‘1’. There’s no way to ‘bust’ in this case - so the final movement will be 1 plus whatever you roll on the second die.

If you roll a ‘2’, you will move 0 if you roll a 1 on the second die, but otherwise will move 4-8 spaces.

If you roll a ‘5’, you will move 0 if you roll a 1-4 on the second die, but will move 10 or 11 if you roll a 5 or 6 on the second die.

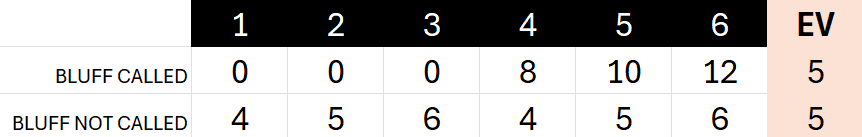

Here’s what it looks like in chart form:

If you roll a 6 on your first roll and always roll the second die, you will move 0 spaces 5 times out of 6, and 12 spaces once.

That puts our EV at 2, which you see in the last column.

This chart shows us that purely from an EV standpoint, we should roll the second die on a 1-4, and not on a 5 or 6.

If you average the EVs, you will get an overall EV for this ‘naive’ strategy (always roll the second die) of 4.08.

If you adopt the ‘optimal’ strategy of rolling the second die on a 1-4, you get this chart:

In this case the average EV is an even ‘5’.

This is higher than both Killer Croc and Bane. So does this mean that this is an unbalanced ability? Maybe - but as a designer there are many things to consider.

First, most players won’t bother going through this math.

Second, Falcone tempts people into making that second roll even if they roll an initial 5 or 6. Sometimes landing on certain other teams is bad, or there are other situational factors at play. Or maybe another player has a reroll ability that can make it much riskier for you to make that second roll.

Third, Falcone’s ability is high variance. Take a look at the row above for if your first roll is a ‘4’. If you reroll (which the strategy recommends), you may move 8, 9 or 10, but half the time you’re moving zero. People don’t like to take that chance.

This is an important lesson: Balance often depends on emotion as much as math. Yes, as a designer you should do the math we went through above (and we did it for this game). But you also need to playtest it and see how it feels in-game, particularly for a light family game like this.

Balance often depends on emotion as much as math.

Riddler - Avoiding Disaster

While emotion certainly plays a role, the math does matter. Doing EV calculations and thinking about strategies can avoid disaster.

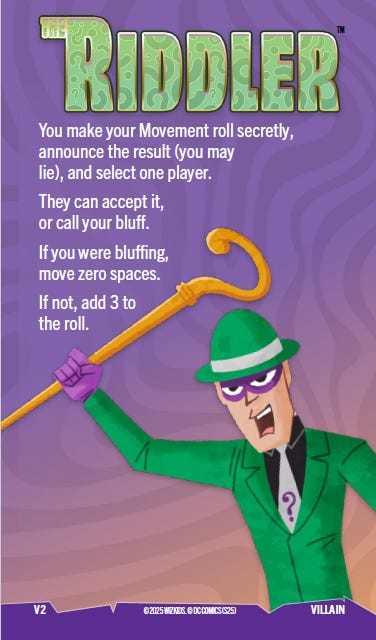

As an example, here is Riddler:

An older version of this ability had you double your die roll if the opponent said you were bluffing and you weren’t.

Let’s take a look at that version of the ability.

After playing with that version of Riddler for a few games, I came up with this strategy:

If you roll a 1, 2, or 3 always bluff and say that you rolled a 4, 5, or 6 (respectively). If you roll a 4, 5, or 6 tell the truth.

So a third of the time I will say ‘4’, a third ‘5’, and a third ‘6’.

Let’s take a look at the expectation values for this strategy:

No matter whether the opponents call your bluff or not, you still on average will move 5!

This strategy is called invariant or a Nash equilibrium, because it doesn’t matter what decision the opponent makes, and you also don’t make a decision. You just follow the algorithm.

I have another word for it - boring. Very boring. The whole point is to try to bluff your opponents. If it makes no difference what they say, it undercuts the entire purpose.

After realizing this, we went back to the drawing board and came up with the +3 on a successful bluff. This eliminates an automatic strategy and forces players to try to outthink each other, which was what we wanted.

Firefly

I will leave you with a question.

As mentioned, in DC Breakout characters don’t escape by themselves. They are part of a team of two.

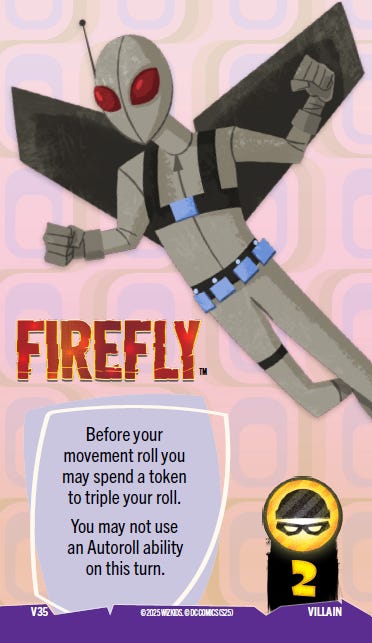

Here is Firefly:

You start the game with two tokens on Firefly, and at the start of each turn you can choose to spend one. If you do, your movement roll is tripled.

Which of the first three above characters - Killer Croc, Bane, Falcone, or Riddler - do you think best synergizes with Firefly? Killer Croc has the lowest EV, but 50% of the time rolls a six. Bane only rolls a six 1/3 of the time, but he very rarely rolls low numbers. And Falcone could move you up to 36 spaces - or absolutely nothing.

These combos, even though the EVs are really close together, feel different - which is just as important (perhaps more) than getting the numbers correct.

So do the math, but don’t be beholden to it. Remember that you are crafting an experience, and that should come first.

So which pair would you like the most? Please leave a comment!!