Today in the United States we celebrate Memorial Day. The purpose of the holiday is to remember those who died while serving in the US military. And yet this original purpose is often forgotten, pushed aside for its status as the unofficial start of summer.

Similarly, as game designers we struggle with getting players to remember rules and procedures. (Even the word “procedure” just puts most people to sleep!)

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve recognized that my short-term memory is not what it used to be, and I have to write more things down. Fortunately, we live in an age where it is very easy to take notes and set up reminders to pop up at the right time and keep us on track. Or perhaps the fact that I have these tools available has caused a reduction in my ability to remember.

Memory, like most things in life, is a skill that can be learned and improved.

The ancients didn’t have the tools we have today. Even just writing something down on a piece of paper was not something done idly. Things to write with and on were both precious.

Instead, they developed memorization techniques, that allowed prodigious feats of memory, like the ability to recite epic poems like the Iliad and Odyssey from memory.

The most well-known of these is the Method of Loci, or the Memory Palace.

The Memory Palace

The idea of the Method of Loci is that you construct a series of physical locations in your mind, preferably ones that you are already familiar with. It could be your home, or it could be a walk that you take frequently.

You then take each thing that you want to memorize and put it at a specific location in your ‘palace’. The theory is that when you think of the location, you will also remember the item you placed there.

A more advanced and effective version of this technique is used by memory masters - people who participate in memory competitions, like memorizing the order of a deck of cards.

For these competitions, people will encode cards into symbols, perhaps a noun or a verb (or both). The book Moonwalking with Einstein goes into great detail on these techniques, which inform the title. Perhaps in your system the Jack of Hearts is “Einstein” and the Eight of Clubs is “Moonwalking”. If you see Jack of Hearts / Eight of Clubs in sequence, and the next spot in your Memory Palace is the sink in your childhood bathroom, you will create a mental picture of Einstein moonwalking next to the bathroom sink.

Advanced competitors use more advanced systems than this, like memorizing “atoms” (like “Einstein”) for pairs or triplets of cards rather than single, so while they need remember more “atomic” images, they don’t have to store as many combined images to memorize a lot of cards or strings of numbers.

The book has full details, and if you’re at all interested in this topic (and you should be), definitely check it out. An excellent read.

While each memory artist has their own system, they all agree that there are a few rules that help make them stick:

The symbols should not overlap that much. Don’t have the eight of spades be a sedan and the seven of spades an SUV. Keep them distinct.

The more outlandish the combined images are, the easier they are to remember. So using things that will create vivid but weird pictures is better. “Farting Nun” is more memorable than “Farting Man”.

Speaking of “Farting Nun”, vulgar images stick better in the brain. Sorry - it’s just science. I guarantee that many of you will be able to remember that there was a GameTek that talked about a Farting Nun.

So how can we apply this to game design?

I can see applicability to two areas we wrestle with:

Creating memorable experiences

Making rules easier to memorize

The Stories We Tell

As designers we want players to not just enjoy their time during the game, but also leave with stories to tell. When I sit down to start a new design, I often think about what stories I want players to remember after the game and try to craft the mechanisms to create those moments.

The Method of Loci teaches us that to create those stories we need to create vivid mental pictures about an event, preferably at a specific location, with an outlandish, incongruous, and outrageous juxtaposition of different imagery.

While sometimes this can arise organically from the players simply interacting and joking with each other, this can be inconsistent and highly dependent on the group. Instead, we can focus on giving players the tools to create the images. These consist of nouns and verbs - objects that are interacting, and how they interact.

One way to achieve this is to simply have outrageous characters or objects, that are intrinsically memorable.

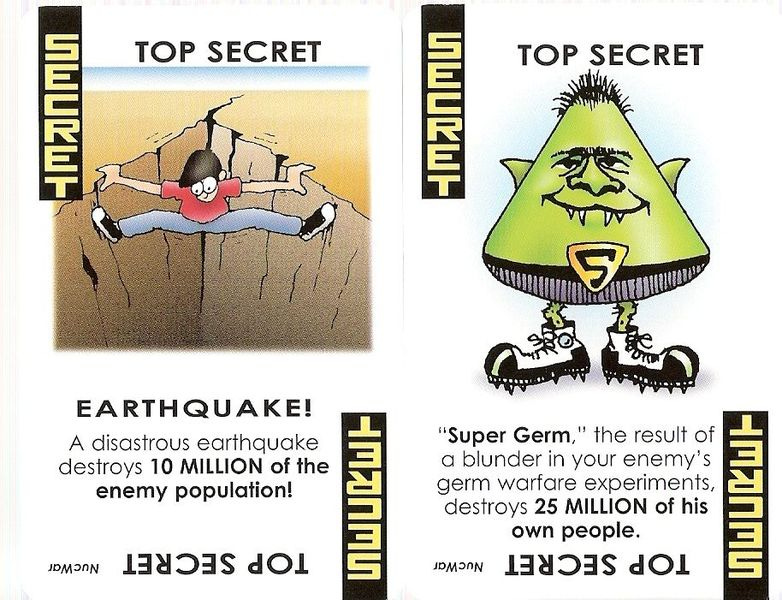

For example, here are two cards from the 1965 game Nuclear War, Earthquake and Super Germ:

For me personally, the main thing I remember from Nuclear War is Super Germ. I even remember the effect of the card. I mean - it’s a weird giant green blob thing with fangs and high-top sneakers. I even remember that he’s wearing sneakers. How could you not remember that?

On the other hand, Until I pulled this screenshot, I had no memory that there was an Earthquake card. I mean, there are tons of games where earthquakes happen. There’s only one Supergerm.

Another method is to create incongruous groupings of well-known or historical characters. Duel of Ages, Unmatched, and Who Would Win are all examples of this technique. “Who Would Win” has you debating questions like “Who would be better at standup comedy - Alexander the Great or Hellen Keller”. Unmatched lets you pit King Arthur and Merlin against Alice in Wonderland and the Jabberwock. These incongruous and anachronistic matchups immediately create memorable mental images that you can carry beyond the game table.

A variation on this is to ascribe characteristics to a character that are not normally associated with them. For example, in the computer game Civilization, each nation is headed up by a leader for the entire game. One of them is Ghandi. And while he generally follows peaceful means, occasionally he could get super-aggressive against a player and launch a full-scale nuclear attack.

Ghandi didn’t nuke the players any more than the other leaders in the game would. Yet “Nuking Ghandi” has achieved meme status. He is memorable because it goes against type.

Another method is combinatorics - relying on random groupings of characteristics, equipment, or statuses. For example, I still remember one game of Tales of the Arabian Nights where my character had been blinded, had an arm chopped off, and then had to fight a Kraken. Not a situation I would have expected!

This relates to a pervious GameTek newsletter about Procedural Generation. If you have twenty statuses, and you can only have one, that’s twenty different situations. But if you can have two, then that’s 380 combinations, which gives more space for narrative to arise.

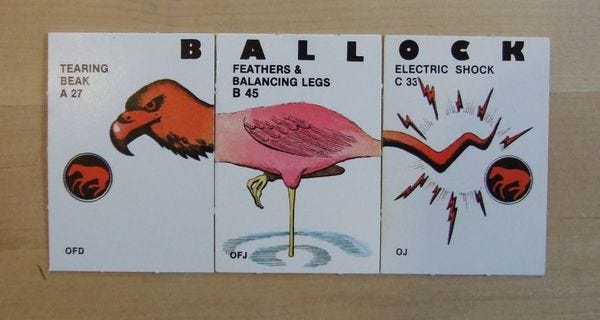

However, to give these combinations a chance to shine, I think they need to incorporate as many ‘real world’ elements as possible. For example, the game Quirks (discussed in that newsletter), has players make plants and animals from three different pieces.

While the game is fun, I never remembered any of the creatures after it ended. This partially may be due to the fact that you only keep them around for a few turns and keep evolving them into new critters.

But I think it is also because the pieces don’t really interact and impact each other. They just modify some stats. The game gives you lots of nouns, but no verbs to speak of. These creatures aren’t doing anything incongruous. They just exist.

The memorable part of my blind, one-armed character from Arabian Nights is that I was fighting a freaking kraken. Just having those statuses wasn’t memorable. It was the action I was performing while I had them.

Fighting a Kraken is cool. Fighting a Kraken while blind and one-armed is memorable.

Making Rules Stick

The other area where Memory Palace techniques might be useful is in making rules easier to retain. Can we teach with outrageous, incongruous, and perhaps vulgar imagery to help them stick?

My thoughts on this are still developing, and this newsletter is always running long. So I am going to open this question up to the readers. Do you have any ideas for how to leverage these techniques?

One possibility that I haven’t really seen is to make examples of play more outlandish - not in the actual rules, but in what happens. What if instead of “Alice” and “Bob” playing each other, it’s King Arthur versus the Jabberwock? In my opinion there’s a lot of opportunity to be creative in rules presentation that will help retention.

What ideas do you have? Please comment below!

Ludology 300

This week marks the 300th episode of Ludology!

I am proud, grateful, and frankly a little shocked that Ludology has reached this milestone. When Ryan and I started the show back in 2011(!) I would not have dared to hope we would reach episode 300. Many thanks to the hosts who carried the torch through the years, and of course all the listeners.

I love Moonwalking with Einstein! Even though I never remembered the logic (or absence thereof) for the card nomenclature...let alone the actual names. I did try using the Memory Palace technique to memorize every amino acid and every disney animated movie...because neither list meant anything to me, and I thought that was a good way to test it for myself. I probably held the amino acids for a couple of years, but the disney ones degraded much, much sooner since I wasn't very invested in them. I probably should be training my memory more, with less mundane lists.

One idea I thought of about making rules memorable is too out there, I don't even think it's applicable to many games. But what if rules (such as action options) are anchored by some weird movement, like a charades-as-rules? It sounds embarrassing, funny, and ideally symbolic, which might help not just the rules giver but the party remember it.

Another idea might just be naming the actual actions, but giving it names that has a story in them, like how playing cards are given names. Weird names, but somehow thematically linked.

I think an example of techniques used to help certain rules stick in your brain is the way Czech Games Edition inserts humour into their rules explanations. It is hard to pull off just right, which is why I suspect that it has not become very popular. It also depends a lot on the tenor of the game, you wouldn't want a grim and brooding setting to have slapstick jokes peppered through out it, that would break the magic circle principle.

When it comes to outrageous stories I see them more as a double edged sword. You want to generate some memorable experiences, but you also want to maintain the general cohesion of the narrative. Often these two can be at odds with one another. If fighting a kraken blind and one-armed is exciting it tends to create a single focal point for the story rather than a particularly interesting episode in a larger progression. Sleeping Gods is the only story game that I have played so far that does a good job in staging its climatic episodes adequately. Again, connecting to a previous discussion, getting these outlandish events to occur close to the conclusion feels more appropriate and neatly tops off a longer memorable adventure.