Salieri

In college I took a science fiction writing class taught by Joe Haldeman, author of the excellent The Forever War. For one assignment we each received a random topic to act as a prompt for a short story.

I was assigned “solar power satellites” that beamed energy to earth via microwaves and wrote an at-best-mediocre story about folks repairing satellites discovering the electronics were being destroyed from nanobots who, I guess, floated in from another star or something.

Like I said - mediocre at best. As were most of the other stories.

However, another student - Allison - was assigned Extra Sensory Perception. And her story was so, so, so good. It was simple - it was set in modern times, but ESP was the norm. And it was framed as the notes of an elementary school teacher who had a young student join the class who did not have ESP - as part of mainstreaming.

The first half of the story talked about the difficulty the student had to adapting. The class was basically silent because, of course, they all just read each other’s minds. It described the changes the teacher tried to make to integrate the new student academically and socially. Ultimately the teacher visits a class of just ‘non-ESP’ students and is amazed at how loud and boisterous the children are.

It was everything science fiction should be. It took this notion of ‘everyone having ESP’ and simply used that as a mirror to get the reader to extrapolate into what it must be like to be a deaf child entering a hearing classroom. It immediately gave the reader empathy for a situation they may not otherwise have had - certainly a perspective I didn’t have. And it was a small, contained story, about a class and a teacher, not some defending-the-earth-from-destruction claptrap. Her story was truly elegant.

I was reminded of that story recently as I just finished reading Babel by R. F. Kuang. I thoroughly enjoyed her Poppy Wars series, but only heard about this novel after an unfortunate controversy when it was excluded from the Hugo Awards held in China (due to concerns about offending the government). Which is ironic if you’ve actually read the book.

Babel is deft and elegant in a very similar way to Allison’s ESP story. It is set in an alternate-history 1830’s England, where magic based on silver bars helps fuel Britain’s colonial empire. The world is very similar to our own, with an overlay of magic, magic however that could stand in for science or technology.

I’ve often viewed science as a form of magic - you sit all day with your head in a book, scribbling on paper, and suddenly figure out a way to alter reality. Much like the stereotypical wizard.

But just this slight tweak lets Kuang approach history and social dynamics from a perspective that is different enough from reality to evoke wonder, but similar enough to let us use it as a prism to better understand both history and the current day.

Which is kind of a magic as well.

Games, Geoff. This Blog is about Games

So what does this have to do with game design?

For most creative professionals, consuming and analyzing other artists’ work is important. It helps you learn about new techniques you were not aware of, a different style, or a creative take on a problem you’ve wrestled with. It has led me to try to codify and share some of those techniques in Building Blocks of Tabletop Game Design, and Achievement Relocked, as well as in this blog.

And I think that over the years I’ve grown into a pretty good game designer. But the more I learn, the more I realize that some designers are operating on a whole other level above me - the same realization I had about Allison’s short story back in college.

The coda to the Allison story is that my reaction was to not try to write fiction again. After that class I never returned to the form.

But I did not do that with game design, in a large part, I believe, because I had that ‘revelation’ of how good some designs were much further along in my design career. Perhaps I was just having too much fun playing games that I wasn’t thinking that deeply, or perhaps the hand of the designer wasn’t as clear to me. But for whatever reason designing a great game seemed much more within reach than writing a great novel.

Which raises the question almost all of us have to wrestle with - what do you do when you realize that you’re very good but not great?

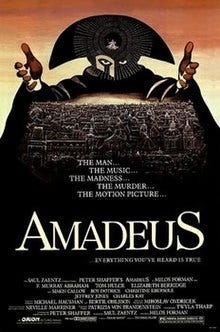

Amadeus

The Academy-award winning 1984 movie Amadeus wrestles with this very question. It fictionalizes the relationship between Antionio Salieri, court composer to the Emperor of Austria, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. When he meets the young Mozart, he is shocked to see that incredible talent paired with an obnoxious and obscene personality.

If you have not seen Amadeus, you absolutely should. It is a deep and moving film.

Spoiler alert for a forty-year-old movie - at the end of the film there’s an intense scene where the two are collaborating on a work when Mozart is too weak to complete it. Even so, Mozart is racing ahead, with Salieri struggling to keep up. It is riveting, as Salieri truly realizes what genius means and that he will never achieve it. It is particularly heart-breaking because a lesser composer than Salieri would not be able to see Mozart’s genius. He’s great enough to know that he will never be exceptional.

I am Salieri

I have come to terms with being a Salieri of game design. I’m immensely proud of my design oeuvre, but I understand now that they are ‘very good’ (maybe even very, very good) but not great. And I’m OK with that. I think a big part of it is getting older - I’m going to be 60 in a few months, and I have the perspective that comes with age.

Which raises the question of who I see as gaming’s Mozart? There are many designers that I am consistently in awe of, who take a thoughtful approach to design and leap above and beyond. But I will restrict myself to one here - Vlaada Chvátil.

For me, the genius of Chvátil is how he effortlessly masters so many different genres. Through the Ages is a best-in-class civ game. Codenames is a best-in-class party game. Mage Knight, Galaxy Trucker - you get the idea.

Frankly, it’s a little annoying.

While I said above that I am comfortable with being Salieri, I would be lying if I didn’t say that I still believe I have a Mozart-level game inside of me. (I can’t bring myself to say ‘Chvátil-level). After I retire from my full-time (non-gaming) job I want to spend more time designing, and I hope that will unlock a final masterwork.

Honestly, probably not. But as I said, I’m OK with that. As I’m writing this I’m listening to Salieri’s work, and you know what - it’s delightful.

Great overview and echos a lot of my own thoughts.

I would also say that for every craft there is essentially always going to be someone better at it. There's only one "best" (if that's even quantifiable) -- and more likely the "best" is only the "best" in an aspect of the craft instead of the whole craft itself.

I also think Vlaada Chvátil is one of those "Mozart-level game designers" too, but even he has had "flops" (in a sense), and to recognize that even some of the "best" out there don't always make the best is an important lesson to learn. Someone's skill isn't measured by their worst game, but by their average or, more likely, their best titles.

There's always room to grow and improve.

Nice analogy. That short story does sound fascinating. Faidutti often says he designs games because he is too lazy to write novels, but I do believe that good novelists might find it more difficult to design a game. And I just happened to rewatch Amadeus two days ago--the first time I'd seen the film since it was in theaters! Good timing. I would love to have Chvatil rework one of my game prototypes the way Mozart reworks the piece Salieri wrote for him in the film! :-)