I was recently at SD Histcon East, an off-shoot of the San Diego Historical Games Convention. The next one is coming up in November, and is worth attending if you have even the slightest interest in historical simulations (which go way beyond war games now).

Shadow

I was giving demos of Kurt Vonnegut’s GHQ (more on that very soon, I promise!) and got into a conversation about our favorite science fiction authors. I brought up Gene Wolfe, author of the series The Book of the New Sun, which begins with Shadow of the Torturer.

Another Jeff (we were flush with Jeffs) recommended I listen to a podcast called Rereading Wolfe, where each episode covers a chapter of the series - in order.

It’s been a fascinating experience. Each chapter is short - around 10 pages - and yet each podcast is from one to two hours. One chapter took three full episodes to work through!

If you haven’t read Wolfe, his prose is clear but dense, and much of it is allegorical. The protagonist is Severian, who is raised by the Torturer’s Guild and ultimately ends up sitting on the throne. (Not a spoiler, as that is revealed in the first chapter).

I’ve read the series twice before this, and I am still learning basic facts that I missed. For example, the hosts point out that the Torturers Tower, where Severian is raised, is a rocket ship. The walls and floor are metal, the bottom is the ‘propulsion chamber’, rooms are described as ‘cabins’, walls as ‘bulkheads’, and windows as ‘ports’. Somehow I just glossed over that and it didn’t register. I had a traditional medieval city in mind, and these hints are spread out over several chapters.

These details are also masked by Wolfe’s consistent use of arcane or completely invented words. So it is easy to think at first that he is using words like ‘bulkhead’ as part of a literary effect, and not literally.

There are definitely mysteries to be plunged into in The Book of the New Sun. Much is not as it seems, and if any series deserves this type of treatment, this is it.

However, the podcast hosts frequently veer into what they freely acknowledge is ‘unhinged speculation’. Every passing character is presumed to perhaps be another character in disguise or related in some deeper way to the story. Every reference is analyzed for connections to other elements. In the first chapter, a corpse is exhumed from a graveyard. We never learn whose body it is, but theories are discussed for close to an hour.

What I find both engaging and frustrating about the psychology of the hosts is that there is an implicit assumption that there is an answer. That there is an actual truth. Of course, though, the ‘truth’ would have had to be inside Gene Wolfe’s head while he was writing.

It is very possible, for example, that Wolfe never had an identity in mind for that body in the graveyard. The identity is not germane to the plot - that of the grave robbers is what is important. And if Wolfe didn’t know who it was (more accurately think it was important enough to decide who it was), then that body has no identity. Yet that possibility is never considered by the hosts. It is decidedly the least fun possibility though, to be sure.

We know that there is no answer. You can argue about it forever, but there is no experiment or test or anything that can be done to see which theory is actually correct, particularly since Mr. Wolfe passed away in 2019.

My wife Susan has a master’s degree in writing and literature, and she points out that writers - great writers in particular - build layers of meanings and symbols into their work without always being conscious of it. And whether the author intended it or not, finding those connections can create resonance for a work to us personally.

But we need to go into the exercise knowing that there is no right answer, and it’s hardly something to argue about. Disagree, perhaps, but not argue.

Pendulum

As humans, we are pattern-seeking machines. We love mysteries and easter eggs. We see faces everywhere we look, for example. This is called pareidolia. Here are some fun examples:

But this can easily lead us astray, as we read more into something than what is there.

This tendency to see more than what is there is artfully deconstructed in Umberto Eco’s wonderful 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum.

Spoiler alert for a 40-year-old book.

The protagonists are researching the Knights Templar, and they uncover a mysterious document from the 1300’s:

a la . . . Saint Jean

36 p charrete de fein

6 . . . entiers avec saiel

p . . . les blancs mantiax

r . . . s . . . chevaliers de Pruins pour la . . . j.nc. 6 foiz 6 en 6 places

chascune foiz 20 a . . . 120 a . . .

iceste est l’ordonation

al donjon li premiers

it li secunz joste iceus qui . . . pans

it al refuge

it a Nostre Dame de l’altre part de l’iau

it a l’ostel des popelicans

it a la pierre

3 foiz 6 avant la feste . . . la Grant Pute.

They fill in the blanks and translate to:

THE (NIGHT OF) SAINT JOHN

36 (YEARS) P(OST) HAY WAIN

6 (MESSAGES) INTACT WITH SEAL

F(OR THE KNIGHTS WITH) THE WHITE CLOAKS [TEMPLARS]

R(ELAP)S(I) OF PROVINS FOR (VAIN)JANCE [REVENGE]

6 TIMES 6 IN SIX PLACES EACH TIME 20 Y(EARS MAKES) 120 Y(EARS)

THIS IS THE PLAN

THE FIRST GO TO THE CASTLE

IT(ERUM) [AGAIN AFTER 120 YEARS] THE SECOND JOIN THOSE (OF THE) BREAD

AGAIN TO THE REFUGE

AGAIN TO OUR LADY BEYOND THE RIVER

AGAIN TO THE HOSTEL OF THE POPELICANS

AGAIN TO THE STONE 3 TIMES 6 [666] BEFORE THE FEAST (OF THE) GREAT WHORE.

They interpret this as a map to the location of the Holy Grail (“the great whore” referring to Revelations and Babylon), and begin a quest to find it. This is the inciting event for the entire book.

Ultimately, they run afoul of another group also involved with the Templars engaged with the same conspiracy.

However, 90% of the way through the book the protagonist shows the message to another character, who looks at it and says:

The Message is ordinary. It’s a laundry list. Come on, let’s read it again. So here is how your Provins message should read:

In Rue Saint Jean:

36 sous for wagons of hay.

Six new lengths of cloth with seal

to rue des Blancs-Manteaux.

Crusaders’ roses to make a jonchée:

six bunches of six in the six following places,

each 20 deniers, making 120 deniers in all.

Here is the order:

the first to the Fort

item the second to those in Porte-aux-Pains

item to the Church of the Refuge

item to the Church of Notre Dame, across the river

item to the old building of the Cathars

item to rue de la Pierre-Ronde.

And three bunches of six before the feast, in the whores ’ street.

“Because they, too, poor things, maybe wanted to celebrate the feast day by making themselves nice little hats of roses.” “My God,” I said. “I think you’re right.” “Of course I’m right. It’s a laundry list, I tell you.”

The entire inciting incident of the book is undercut right at the end, because, as Eco says “the simplest explanation is always the best”.

And yet the conspiracy theory, the misreading of the passage, takes on a life of its own and ‘becomes’ true and has real consequences because enough people believe in it.

It’s a wonderful book. Highly recommended.

Our ability and desire to make these kinds of connections also underlies the popularity of Escape Rooms and related board games like the Exit series, and the upcoming Magnus Protocol Mysteries (designed by my daughter Sydney). We go into these knowing that there is a mystery and there is an answer and (if it is well designed) that the clues are there for us to figure out.

Unfortunately, if there’s one thing the internet has brought to us, it’s a flood of conspiracy theories, and those too trusting and eager to believe them.

Moon

Another game that explores the idea of a ‘conspiracy in a box’ is City of Six Moons, by Amabel Holland.

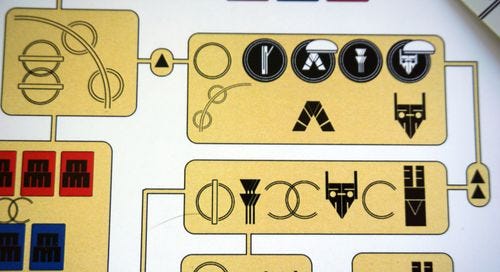

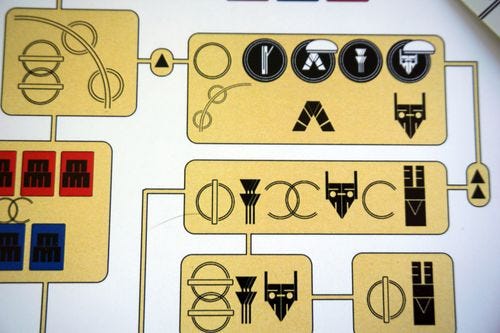

The conceit of City of Six Moons is that it’s an alien civilization game that comes from an alien civilization. There are no rules in a human language - they are presented as pictograms. It is up to you to figure out what the rules are.

(Part of a rules page from City of Six Moons above)

This is a fascinating idea that evokes archeologists trying to piece together the rules for ancient games. The ‘rules’ that you read for games like Senet and Mehen are guesses at best, although they are often presented as definitive. It is almost certain there were regional and temporal differences in how these games were played.

I mean, what are the rules for Monopoly? You ask ten people you’ll get ten different answers.

The Digital Ludeme project is attempting to use a process based on archeology, history, and statistics to piece together how rules evolved and spread, and possibly be able to back in to how certain games may have been played.

Amabel wrote an excellent designer diary for Six Moons which is worth a read. It implies that there is an answer - that the corpse in the graveyard actually has an identity.

However, a few months after the game some people thought some of the diagrams seemed ambiguous. In response she posted that:

I can say that everything in the rulebook is intended to be there. Whether or not it's confusing or ambiguous for the people of this planet is another question altogether.

Some people got very upset at that. They wanted there to be a definitive, right answer.

One BGG user posted:

I want to believe there is a great game in there. And I want to believe that the rules we were given are complete and accurate enough that we could get there, or at least close to it.

But I more and more get the feeling that even if there is, the rules have gone beyond simple obfuscation and into deliberate misdirection. IE, the game the rules describe is NOT necessarily the "indescribably great game" that was originally created. That even with the most generous interpretations, it will fall flat because the intentional changes remove key (even if subtle) factors into how it plays out.

Responses like the one above leave me less certain that it's even possible to find the original game.

If the reason for the failure to translate is on us, the "players", trying to make sense of it, fine. If the reason for the failure is that the rules themselves are intentionally ambiguous, meaning that none of the interpretations are correct nor incorrect. That's what I meant when I said "Ambiguous means 'we' are missing something" - the misinterpretation is on us, the player. But if the ambiguity was intentional for the sake only of having mulitple VALID meanings, then there is no "one game" underneath it.

To use the faulty Sudoku example given elsewhere; if the deciphering is like filling in a Sudoku grid, and completing it results in a complete ruleset, it would be as if the grid we were given only has a few numbers written in it, in such a way that there are multiple (dozens? hundreds?) of ways to fill out the missing parts. Even if one of those was the intended answer, there'd be no way to know. And if one of the numbers was intentionally changed to something else, then it would be impossible to get the intended answer.

Later, she even posted that as the game became more popular and she hand-built more sets (all sets are put together on demand) it was possible there were different versions of the rules out there.

In another thread, someone was quite upset about this possibility. I can only say that if two people have slightly different versions of the rules, then in isolation they each have a solvable puzzle and playable game. If those two people wish to compare notes to decide which is "real", well, both are real. If they want to go further to try to synthesize the two in pursuit of an "optimal" version, they can, though that might be a third, different, thing, and does not, as I see it, impact one's ability to experience the version they have.

I absolutely LOVE that the user response above starts with - and then repeats - I WANT TO BELIEVE, which is the rallying cry of conspiracy enthusiasts and X-Files fans throughout time.

One of the dirty little secrets of game design (which may not be dirty, nor little, nor a secret) is that most games of a certain complexity include rules that could have gone different ways without impacting game play. Maybe there's a tie break rule, or how many cards you have in your hand, or a limit on a token, or something like that. The designer needs to just come down with a decision on what it should be, but often there is very little difference in the gameplay regardless of the option chosen.

So I think this discussion - and really the whole concept of this game - is fascinating in that there's this desire for there to be a 'right' answer, when in reality there is no 'right' answer in a very strong sense for just about any game. In Ticket to Ride would the game change if the number of train tokens each player gets is one or two higher or lower? Or if there were a couple of more or fewer locomotive cards in the deck? Not really, no. And did Moon test all the possible variations to find the ‘best’ version? No.

And some players would enjoy the game better if these were tweaked, and some would like it less. At some point the designer just makes the call, but that doesn't mean it's 'right' or the platonic ideal of what the game is expressing.

If there are two or more different interpretations, or games, that come out of the City of Six Moon rules, or if there are different rules sets floating around out there, in my opinion that's fine and cool and totally part of the intent of the project. I don't see this as simply a sudoku with one correct answer. Games aren't logical constructs like that. Even though (if) Amabel has one version in mind, that doesn't mean that's 'right'. What if another interpretation results in a game that is tighter, more fun, more challenging, whatever metric you're looking at?

Isn't that an equally 'right' answer?

I think it's only valid to the extent that players agree on which version they're playing, as that agreement on the rules is what allows players to play together in any useful sense of the word. Even in games that leave room for unarbitrated differences of interpretation (GM-less RPGs, narrative miniature campaigns), there's an underlying agreement between the players as to what type of game the one they are playing should be, which guides them in deciding which of multiple interpretations sounds best in the moment, allowing them to continue. When players can't agree on what should happen next, at least one player will feel cheated by the outcome. And when one player diliberately obfuscates the nature of the game being played, that player _intends_ to cheat the others.