As you may know, I am fascinated by player psychology, and tools that designers can leverage to tailor the experience for the players. So fascinated, in fact, that I wrote a book about it: Achievement Relocked. In the process of developing that book I came up with an approach I call Staggered Goal Engagement Theory (SGET) - which I understand is an absolutely terrible name that will never catch on.

But it has given me another lens to look at my designs with, to see what may be added to pump up the design.

Before I get to exactly what SGET is, first some background information, adapted from Achievement Relocked.

Car Wash Experiment

In 2004, researchers Joseph Nunes and Xavier Dreze conducted an experiment at a California car wash. They handed out 300 loyalty cards. Half of them needed eight stamps to earn a free car wash. The other half needed ten stamps, but two of the spots were already stamped. So, in both cases, eight additional stamps were required to earn the free wash.

Then they sat back to see how many customers completed the cards.

19% of the customers with the eight-stamp cards redeemed them for a free car wash. But 34% of those who had the ten-stamp cards redeemed theirs. Even though consumers had to return to the car wash an equal number of times, almost double the number of people who got the two free starter stamps completed the task.

Giving the consumers a head start made them much more likely to complete the task. The researchers called this the endowed progress effect. Giving progress to people made them more invested in the program. It made them think that they already had started the task and gave them a sense of commitment.

Endowed progress is yet another aspect of Loss Aversion - when people are more emotional about losses than gains. Nunes and Dreze chose the adjective “endowed” deliberately. The act of giving something to someone triggers a possessive, emotional response. In the car wash experiment, it made people feel like they had something to lose—and also made them more likely to “finish the level,” even if it was something as mundane as getting eight car washes.

Liquor Store Experiment

Before we get into the game design implications of endowed progress, let’s take a quick look at another version of the car wash experiment that Nunes and Dreze reported on as part of their original paper.

The researchers hypothesized that if you just gave someone a bonus, a head start, without any type of explanation about why you were doing so, people would be suspicious about your motivations and be less likely to cash it in.

This experiment was performed in a liquor store. Some customers were told that they needed to purchase a certain dollar value of liquor in order to receive a bonus bottle. Some people were just started on the program, while others were given a $10 head start toward the goal. Of those who received the $10 bonus, some just got it, and others were given an explanation about the store doing a special promotion for an upcoming holiday.

Another group, instead of needing to achieve a certain dollar value, were awarded points with each bottle purchased, and when reaching a point threshold would earn a bonus bottle. Again, some people were given bonus points to start with, and others were not. And, of those who received the bonus, some were given an explanation, and others were not.

The results were intriguing and only partially supported the suppositions of the researchers.

When people received the monetary value as a starting bonus, the endowed progress effect only kicked in when they were given an explanation. Those who just got the starting purchases on their card did not feel the urge to complete the task.

However, when the points system was used, the explanation had no effect. The endowment effect was triggered either way.

This underscores an effect casinos take advantage of. The use of an artificial currency—points in this case, chips for the casino—puts people into a different head space than money does. People need to be separated from the value in order for many of these psychological effects to manifest. The value of money is too tangible.

Experience in RPGs

Dungeons and Dragons enshrined the concept of characters gaining experience points to gain levels. With that innovation, it also created perhaps the most commonly-used endowed progress effect in gaming.

Here’s a typical chart showing a player’s level when they gain a certain number of experience points:

0 XP: Level 1

1,000 XP: Level 2

3,000 XP: Level 3

6,000 XP: Level 4

10,000 XP: Level 5

If a character has 1,200 experience, they are level 2.

Very rarely do players hit a level threshold exactly. Almost always, they overshoot the threshold and are already on the road toward the next level. This creates a momentum, as players are almost never at the beginning of the road to the next milestone. They are always a few steps along—probably not many, but enough to trigger the psychology of having started on a journey and being committed. There’s no time to “take a breath,” as it were, at a level break and to ponder the long road to the next level. You are almost always endowed with some progress toward the next goal.

This momentum carries players from goal to goal and maintains engagement. Over the years, the technique has been refined and incorporated across a variety of genres.

One improvement in game design has been shortening the distance between goals. Moving from level 9 to 10 in D&D can take quite a bit of in-game time. Designers have been shrinking this timeline, increasing the impact of having partially-completed goals.

An excellent example of this can be seen in the computer game Civilization. Civilization is a turn-based game, but the turns are very short—and, critically, the duration of most things you want to do requires multiple turns. For example, research projects may take 10 turns to complete, a new building for your city may take 8 turns, or moving a settler to found a city may take 12 turns. As you get more cities and grow your civilization, you have more and more of these projects running in parallel. But because they all end at different times, you always have some short-term goal that is in progress. Each of these goals in and of itself gives psychological impetus to the game. But having so many of them in different stages creates a compulsion, a palpable forward momentum that forces the player to continue on, turn after turn.

It’s no surprise that Civilization earned a reputation for players spending marathon sessions playing it hour after hour, wanting to get in “just one more turn.” The combination of short turns and staggered multi-turn projects taps directly into the psychology of endowed progress to keep players engaged and wanting to bring things to completion.

Staggered Goal Engagement Theory

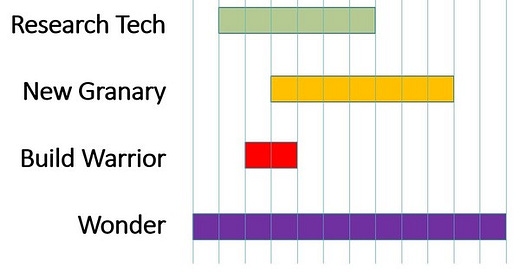

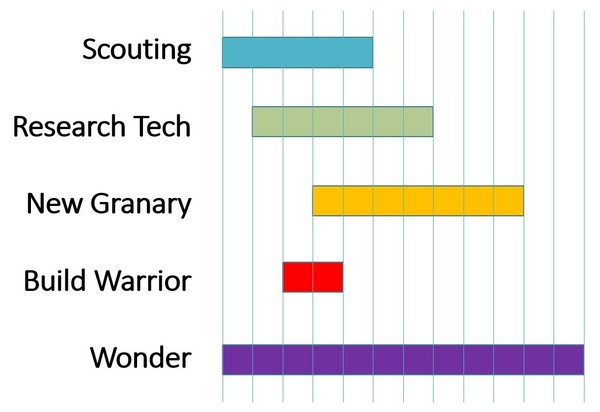

This is the key design element of SGET - Multiple projects/goals that end at different times. Here's a diagram with some typical Civ-style projects:

As small project ends, other projects are close to completion. Having multiple, overlapping projects is at the heart of building momentum to keep players moving forward.

Even though they are typically much shorter than RPGs or computer games like Civilization, board games have also been adopting these ideas. In general, turn structures have become shorter and more interleaved. It is rare to see a game like the war games of the 1970s and 80s, where one player would take an hour to perform their move while the other simply watched. Turns are much more bite-sized. Tactical games like Panzerblitz, where each player had long turns while their tanks dashed from bush to bush, have now been replaced by games like Combat Commander and Infinity. These newer games have activation systems where movement distances are short, destinations can rarely be reached in one turn, and opponents have ample opportunity to react to partially-hatched schemes. Like in Civilization, this carries the players forward.

In my own game, The Fog of War, a simulation of the European theater of World War II, players cannot just launch attacks. Instead, they need to plan what are called “operations.” Forces in The Fog of War are represented by cards. Players also have a deck of cards representing the different locations they can attack. To plan an operation, they place a stack of cards that include the forces they want to attack with and the target location. But the operation cannot be launched right away. Players must wait at least two turns before they can launch the attack, and they may wait up to six turns. Each turn you wait, you may add more strength to the operation—but your opponent may conduct intelligence against them in an attempt to learn their destination.

Also, you are only allowed to create one new operation each turn. This evokes the same feeling seen in Civilization, where you have a series of partially-finished projects with staggered end points.

The Fog of War also features short turns. Players have hands of three cards. On their turn, they can play any number of them then draw back up to three. For experienced players, a turn usually takes less than a minute. Compare that with Third Reich, where one player’s turn could easily take an hour. Turns in Fog move back and forth quickly, which, as in Civilization, keeps the players engaged and gives the game a strong feeling of forward progress and momentum.

Through the years, designers of all types of games—video games, tabletop games, card games, and more—have realized the power of short actions that extend across turns to motivate players. Games where players have extremely long turns while other players watch have thankfully become a small minority of new designs.

Anti-SGET Games

There are project-based games that don't take advantage of this technique, and I think they suffer for it.

There are many games where you are, for example, collecting resources to purchase a card, upgrade, or other benefit. You work hard and accumulate what you need, but then after you get enough resources and cash them in, you are back to square one and have to climb the mountain all over again to buy the next card, or what have you.

Personally, I find these games very frustrating. I'm not going to name names, but I'm sure you know of several that fit into this mold. They take what should be a mini-climactic point - buying a VP card, for example - and give it a negative spin because you are now very far away again from getting the next one. They have a real 'rinse and repeat' flavor which does not work for me.

In your own designs - or simply when you are playing someone else's - look for these overlapping projects and goals. Don't leave the player in a position where they have completed all of their goals and are returned back to the bottom of the mountain. Always put them partway on the path towards their next objective.

Really enjoyed this article! This concept reminds me a lot of "Flow" in games. This idea that a game should put the player in a state of flow so that difficulty isn't too hard or too easy. I think the two ideas are actually very similar. What I can't figure out is whether flow is a tool for SGET or if SGET is a tool for flow. I'm leaning towards the latter: you can use staggered goals in order to promote and drive flow in games. Curious of your thoughts!

Interesting read as always Geoff.

I'm wondering if you're critical of archetypal engine builders --let's take Dominion's base game for example-- where there is a pivot in the game into buying VP and, critically, where that VP doesn't lead you into the next goal, or where it even slows your momentum overall. "Classic" deckbuilding (where the card goes into your discard instead of your hand) has a delayed momentum to begin with in that you may not see the fruits of your labor for a couple turns, but then the final (second?) act of the game is players mostly just running the engine they've built. They're essentially comparing how well those engines run against each other at this point, but no more of this momentum you're speaking of is being put into the system.

I guess my question overall is if you think Dominion's base game, for example, would be more fun if the building and momentum continued through the end of the game. Is the SGET hypothesis that it objectively makes for a more fun experience (in any game with an engine element) the more that it's used?