The Incan Gold Experiment Part 2 - The Results

In last week’s GameTek I described a thought experiment about retheming Incan Gold as a firefighting game. A few years after I first published that, I was contacted by Dr. Stephen Blessing at the University of Tampa, asking for my permission to actually conduct the study! I was thrilled of course and am pleased to present those results here.

BUT FIRST: A quick commercial announcement:

PlayToZ Games, a new game company that I am an investor in, has just launched their first Kickstarter - a new edition of Ascending Empires. PlayToZ was started by Zev Shlasinger of Z-Man Games-fame, who first printed Pandemic, and introduced Agricola to the North American market. I’ve truly always been a fan of Ascending Empires and am very excited to try out this fantastic new version. Please check it out if you get a chance!

The Incan Gold Experiment

If you haven’t had a chance, please go back and read the last issue of GameTek, which goes into detail on the background behind this experiment.

But a quick summary: Incan Gold is a push-your-luck game, where each round you decide whether to run out of the cave you’re exploring, locking in your earnings so far, or press on, in the hopes of finding even more treasure. I posited that the Indiana-Jones theme subtly impacted how long players stayed in the cave, and that if were, for example, a game about saving people from a fire, players would tend to stay longer.

To perform this experiment, Blessing et al made three computer versions of the game - a standard Incan Gold version, the Firefighter version, which they called “Emergency 911”, and a non-themed version called “No Whammies”.

They had several hundred people play a version of the game, with the same sequence of card draws. Each person played the same version of the game four times, and each game (game #1, game#2, etc) was the same for each player - the deck was stacked by the computer. So every single game #1, regardless of theme and player, had exactly the same deck order.

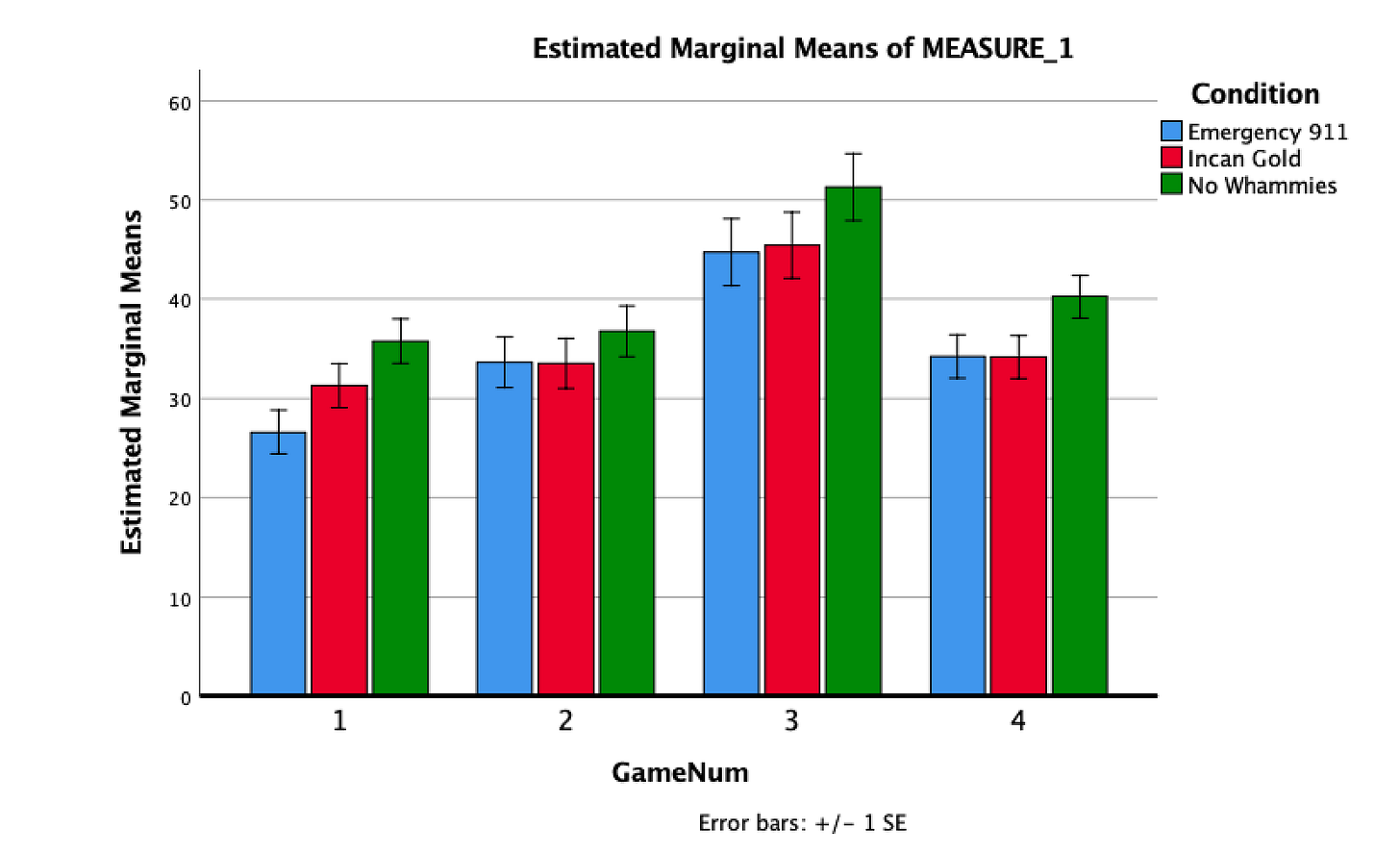

The first chart shows the averages of the final scores:

The blue bars (first in each group) are Emergency 911, the red (middle) bars are Incan Gold, and the green bars are No Whammies.

A few things jump out in this chart. In all cases, players scored the highest in the non-themed version than they did in the themed versions. In game 1, firefighters did do worse than in the other versions.

However, the differences between Incan Gold and Emergency basically vanished in the next three games.

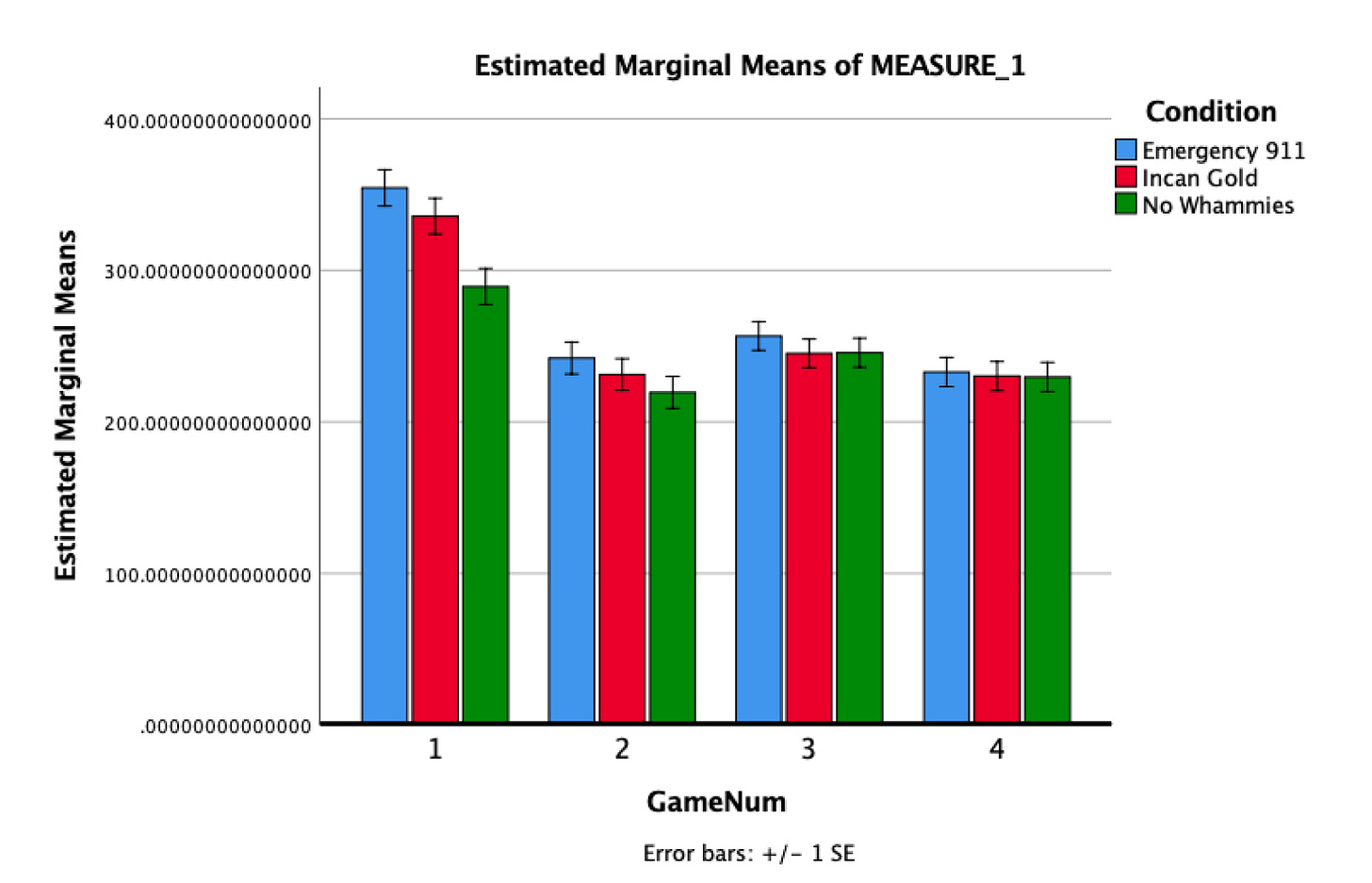

The next chart shows the amount of time players took to complete the game:

Play time decreases with multiple plays, as expected. But the impact of theme is clear in this chart. In all cases, players took the longest playing Emergency 911, then Incan Gold, and finally No Whammies.

Again, the games are exactly the same rules, the deck order the same - everything is identical except the theming.

This strongly implies that the ‘serious’ theme of Emergency 911 is making the players more carefully consider their choice, agonizing over it a bit more. And this trend continues across every game. It shrinks as time goes on, but it is still there.

Ironically, as the first graph shows, that extra time taken to play is not translating into a better score. Emergency 911 players consistently take the longest time to play, and do the worst.

I think this clearly shows the impact that theme is having, particularly with the first plays.

Also, in general, as plays went on, the differences between the different themes faded. It was still there, but over time it seems that more players looked past the theme and focused on the mechanics.

One of the other factors that was tested in these experiments was whether the personalities of the participants affected how they played. People self-described themselves on a standard personality questionnaire before the games were played, and no correlation was found between any personality measure and how likely they were to play in a risky or conservative way. There was no measurable impact.

After the experiment was concluded, participants were asked to rate certain aspects of the game. The experiment was performed twice, with slightly different conditions, so the results are split out:

Higher numbers mean they agree more with the statement.

You can see that Theme didn’t impact the enjoyment of the game that much. Where it did make a large, consistent difference is in how difficult the game was to understand. In both cases Adventure and Firefighter. In both experiments the Incan Gold theme was the easiest for players to understand. This is suggestive, as it is what the game mechanics were designed for, so one could argue that it is a better ‘fit’ than Firefighter, and players sensed that. They were able to slot the rules better into their mental picture of that type of environment. Firefighter was better, but abstract was ranked as most difficult to understand in both cases.

I’ve always believed that better thematic integration makes games easier to learn, but it’s nice to have empirical data to back up that intuition.

It is also interesting to see that Firefighter was ranked lowest on “I would play the game again” and highest on “I was engaged in the game”. One would think that those two would be correlated, but in the same direction - if people were more engaged, they would want to play again. But we see the opposite here.

This may be related to the emotional stress response to the subject matter. Yes, rescuing people from a burning building is engaging - but I wouldn’t want to do it again. I certainly feel that with certain moves. Schindler’s List was a great film, but I doubt I’ll ever watch it again. On the other hand I’ve seen Airplane! dozens of times. (Yes, I’m shallow).

So grabbing the players and giving them an intense emotional experience may engage them at the time, but may be counterproductive towards the game hitting the table frequently. Some food for thought.

Takeaways:

Theme matters

Thinking longer doesn’t mean doing better

Thematic-mechanic integration does indeed make games easier to learn

Engagement doesn’t equal desire to play again

Hi all! This is Stephen Blessing, the person who did the experiment. Special shout-out to my undergrad assistant who tested most of the participants, Elena Sarkosky. She also did the additional art we created for the variants and the backdrop (I didn't know when she came on board she had some artistic talents!).

If you have questions, feel free to post here obviously, or send me an email at sblessing at ut.edu. A pre-print of the paper can also be found here: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/syjm9 (this takes you to an ArXiv site; this version only has the first experiment). This will find a journal home someday, but it kind of falls between the cracks of topics that cog psych journals find interesting (where I mostly publish).

Thanks for everyone's interest!

I have to agree with Matt. It appears you may be over-generalizing from the data. Definitely by Game 4, there are no differences between time spent playing the games. I think one big takeaway would be Theme hardly matters. (by game 4, theme doesn't seem to be impacting time spent processing - however, it might actually still be hindering performance).

In Table 1, the "rules are difficult to understand" is insignificant across all conditions - at least with a cell size of 100. Yes, there is a significant difference in Table 2 between abstract and adventures, but I wouldn't find this one difference a compelling finding - after all, there are 33 pairwise comparisons - I'm not surprised that one is significant...

I think it is an interesting study. One question that intrigues me is since each game was fixed, we know what the optimal series of choices was for each game (either based upon card outcome or by expected values updated after each card is revealed). When participants performed sub-optimally in each condition, we could check if it was because whether they took too much or two little risk in their decisions to stay or return to base camp/leave the building. An interesting analysis would be to see if players acted more "riskily" in one condition over another.