Top 10 Unnecessary Components

and why they are necessary

I’ve played a lot of games over the years, and one thing I always enjoy seeing is a Completely Unnecessary Component. This is something that either serves no mechanical purpose in the game, or could be done in a much simpler way.

I thought it would be fun to put together the definitive, completely 100% accurate list of the Top 10 Unnecessary Components - and see if we can learn something along the way.

Let’s jump right in!

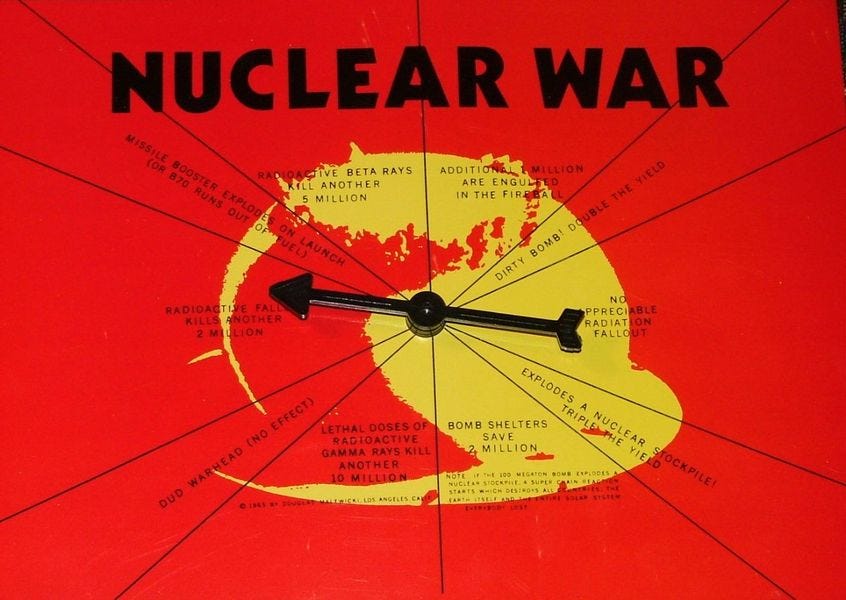

#10: Nuclear War: Spinner (1965, Douglas Malewicki)

Flying Buffalo released the card game Nuclear War in 1965. The theme is very dark: at the start of the game each player is dealt ‘population cards’ representing from 1 to 25 million people. You then use propaganda, events, and the titular nukes to knock your opponents’ population to zero.

When a player gets eliminated they get a ‘final retaliation’ strike, where they can launch everything they have in their hand at anyone they like. If that eliminates other players, they get final retaliation, and so on.

Often games end up with no winners. I played in a tournament at Origins in the 1980’s where we had to play over ten games until someone finally won.

Each warhead card kills a certain amount of population. But after launching you use the Nuclear War Spinner to determine what actually happens. The results range from Dud Warhead (No effect) to Bomb Shelters Save 2 million to the dreaded Explodes a Nuclear Stockpile: Triple the Yield.

This spinner could have been easily replaced with special dice, or a chart. but the choice underscores the satire in the game. The spinner immediately puts the players in the mindset of playing a children’s game, which is a stark counterpoint to the subject matter.

#9: Shogun: Turn Order Swords (1986, Mike Gray)

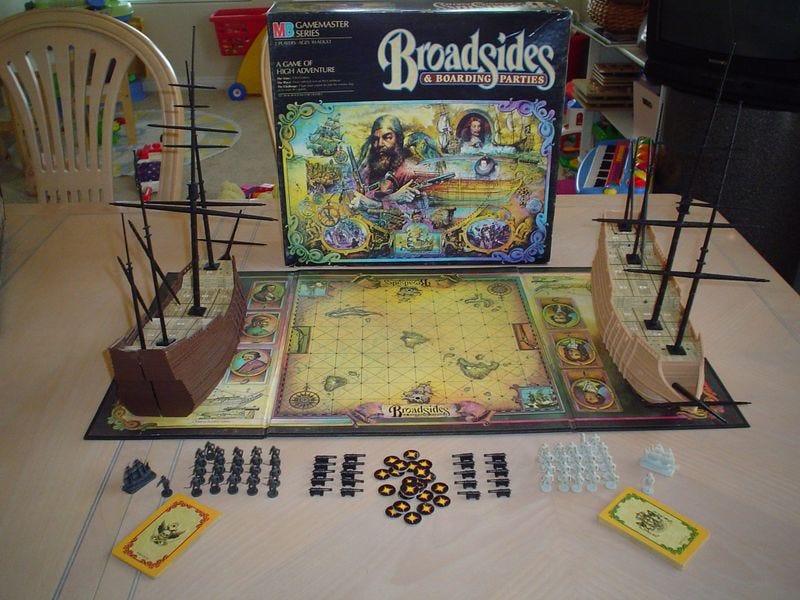

Shogun (later released as Samurai Swords and Ikusa) was part of the Gamemaster Series from Hasbro that started with Axis and Allies. They were filled with tons of plastic, styrofoam, and other non-biodegradable components - including complete ship models for Broadsides & Boarding Parties:

While that deserves consideration for this list, the swords in Shogun hold a special place in my heart.

The game comes with five swords, and they have from one to five raised diamonds along the blade. These swords are used to determine - player order. That’s it. And they weren’t great at that function, as the diamonds were difficult to see on the black swords.

They are so unnecessary that they were not included in the later “Ikusa” version of the game.

Yet, there is such joy in pulling those swords and placing them in the little Styrofoam sword block so the other players can see the current turn order that I would never play it any other way.

#8: UBOOT: Three-Dimensional Board (2019, Bartosz Pluta & Artur Salwarowski)

I considered putting the aforementioned Broadsides & Boarding Parties into this slot, but UBOOT had to take the slot for board-that-is-complete-over-the-top. Just feast your eyes on this 3D sub diorama:

The initial construction of the board is a whole project unto itself. But the ‘dollhouse’ factor here attracts people immediately. Any discussion about games with table presence must include UBOOT, which has not just the 3D sub model but also instruments, gauges, dials, and more. Just take a look at the protractor in the left side of the picture above that you use to plot your course. How immersive is that?

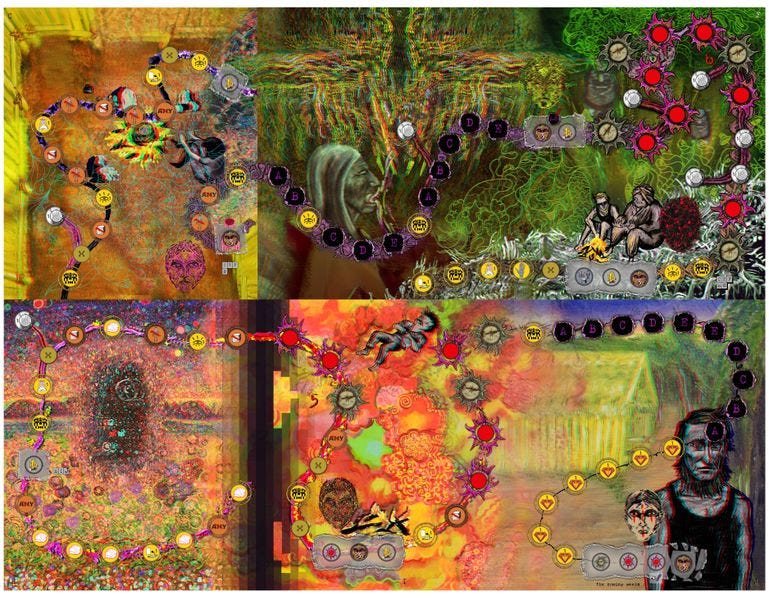

#7: The Mushroom Eaters: 3D Glasses (2013, Nate Hayden)

The shaman is old and fading, and their successor must be chosen. The players all embark on a psychedelic journey to determine who will be selected as the new shaman.

Not your average theme. And not your average game. Of particular interest here is the board. It has two unique features. First, it starts out folded and gradually unfolds and twists on itself as players advance along the path. It reveals new vistas as players advance through it and different panels are opened and closed and folded back against themselves.

It’s very difficult to describe, and I was unable to find a video clearly showing how the board works (and lacked the ambition to film one myself). This is the closest, with the board being shown around the halfway mark:

This video has the advantage of featuring people opening the box who had no idea what the game was about, and being baffled, and then amazed and intrigued as they realized what was happening.

But while the clever folding of the board serves a somewhat mechanical purpose, the other feature is unnecessary. The board is printed in red/blue anaglyph, and the players wear 3d glasses while playing.

While mechanically unnecessary, wearing these glasses is intensely immersive, and immediately transports the players into a world where they are literally working their way through a drug trip.

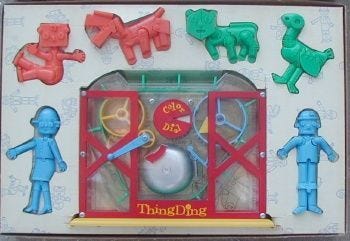

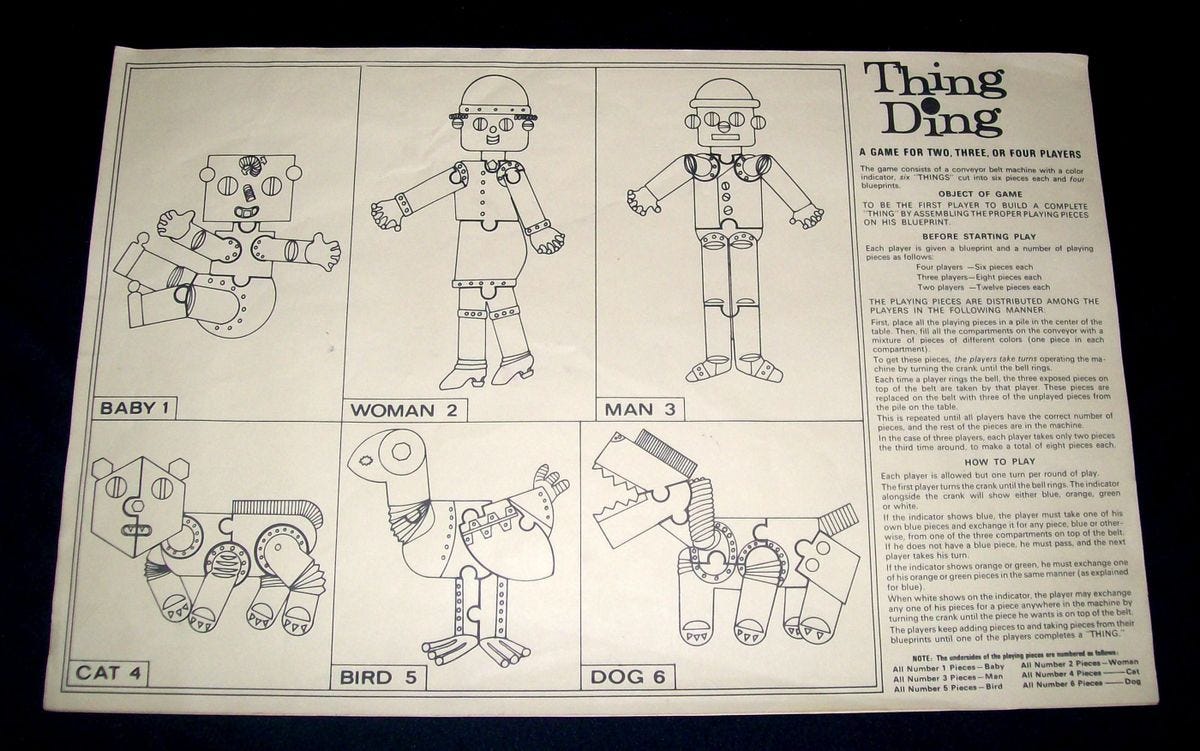

#6: Thing Ding: The Thing Ding Machine (1966, Marvin Glass)

I will be surprised if anyone reading this is aware of this game - if you are, please let me know! But it was a staple of my childhood.

There are six robots - robot mom, dad, baby, dog, cat, and bird, each of which is made up of six pieces. The pieces were mixed up and seeded into the Thing Ding machine, in the center of the above picture. It consists of a conveyer belt broken up into slots, and you put one piece into each slot.

On your turn you rotate the crank, which moves the conveyor belt, until the bell rings. You then see what color is shown on the wheel, and you have to swap a piece of that color for one that is showing on top of the machine (if there is one). The first person to complete a robot by getting all six of its pieces wins the game.

As a game, there is very little going on. But the magic is in the machine, particularly since it was clear and you could see the gears and pieces inside. We could play with the toy for hours, watching all the pieces move around the interior.

#5: Scotland Yard: The Visor (1983, Burggraf, Garrels, et al)

An early winner of the Spiel des Jahres Award, Scotland Yard has the well-deserved status as a classic. In this one-vs-many game, one player is the elusive Mr. X, who is trying to evade the detectives.

While it’s a lot of fun playing Mr. X and trying to outwit the detectives, the best part is that you get to wear this neato visor:

The visor ostensibly does serve a functional purpose in the game. Theoretically it disguises exactly where you are looking at when you look at the board, so you don’t have to worry (as much) about the detectives trying to get information that way.

But really, it’s just cool to wear.

It became such an iconic part of Scotland Yard that the 20th anniversary edition came with actual baseball caps to replace the visor:

Donning the visor immediately puts you into the headspace of the dastardly mastermind.

Were there other ways to accomplish what the visor and hat do? Yes. Would they have been as cool? No.

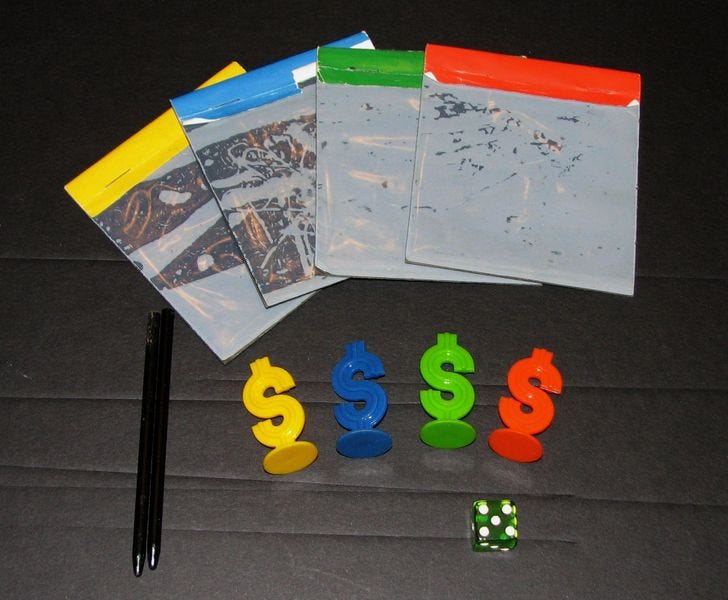

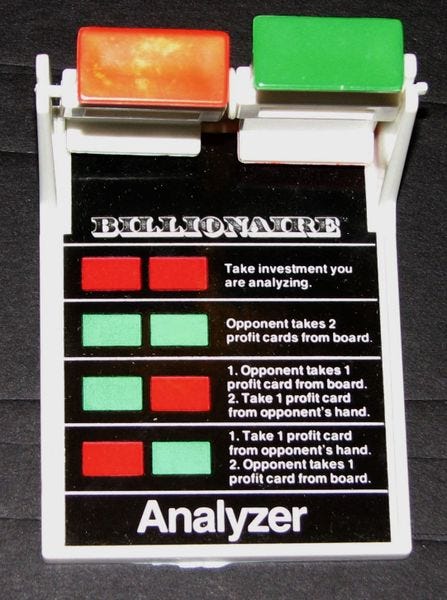

#4: Billionaire: The Analyzer (1973, Marvin Glass)

Second game on the list from Marvin Glass! Billionaire is another game many of you may not be familiar with. It is a class roll-and-move game that has you moving around a track buying properties, but there’s a lot more going on than in Monopoly or similar titles. There’s a robust auction section where you write secret bids on those carbon pads that you lift to erase - now replaced with boring whiteboards:

Those were fun to use. But the best part of the game was “The Analyzer”:

I think you can literally pinpoint the year this game came out from the font used on “Analyzer”.

At certain points you could try to ‘analyze’ an investment that belonged to an opponent. To do so you spun those two flippers that had green and red ends. Depending on the combination, various effects happen.

The order of the colors matters - red / green is different then green / red - so this is essentially a needlessly elaborate D4. There are a zillion (billion?) ways to do this other than this complex plastic contraption,

But they decided to go with that, and thank goodness they did. As you can imagine, when you spin the Analyzer it can take a little while to come to a stop, so it amps up the tension. And for kids that didn’t know anything about how high finance actually worked in the real world, it seemed like we were doing something high tech.

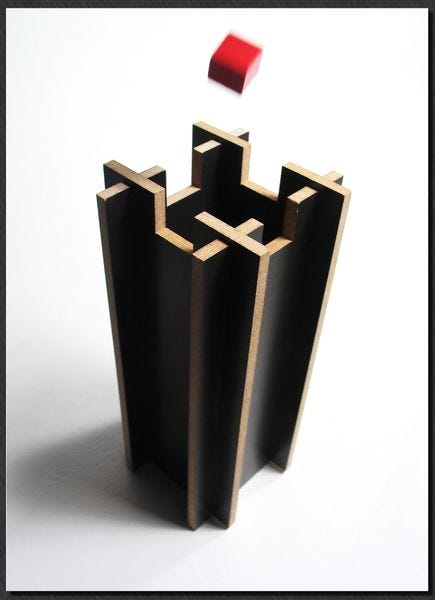

#3: El Grande: The Castillo (1995, Wolfgang Kramer and Richard Ulrich)

El Grande is one of the pinnacles of the European school of game design. Simple rules, tight game play, and vicious competition. It often feels like the proverbial knife fight in a phone booth, but it offers plenty of opportunities for clever plays.

For those of you who have not played El Grande (and shame on you), it is played on a map of Spain. It is basically just cubes and cards, except for one feature that towers (literally) above the board - The Castillo.

At certain times you can place cubes into the Castillo. And during scoring rounds each player secretly picks which province they want to deploy their cubes to. It leads to tremendous feelings of yomi as you try to outguess the other players.

As an aside, the castillo was one of the instigators of the debate about ‘hidden but trackable’ information in the gaming community. It is always public knowledge how many cubes of each color are going into the castillo. But you can never look in there, and just need to remember them. But should people be allowed to take notes?

I wrote about my take on “hidden but trackable” information in the GameTek book, so I won’t go into here. But if you’re interested let me know and I can reprint it.

There is no reason the castillo needs to be as large as it is. Yes, it makes it basically impossible to see the cubes inside, but there are other less imposing ways to do that.

But I can’t imagine it any other way. The size of it adds to the joy of throwing cubes in, and its dominating presence makes it a constant reminder that those cubes are coming back into play to mess up your plans.

#2: Los Mampfos: Pooping Donkey (2006, Rudiger & Maja Dorn)

Los Mampfos is similar in concept to the El Grande Castillo in that you are putting different colors into a hidden container and need to remember what’s in there.

Except in this case you are feeding different colored pellets to a donkey and need to predict what colors will be pooped out.

Yes, pooped out. At certain points the donkey’s tail is lifted up and the pellets shaken out. There are three donkeys moving around the track, all eating different pieces, so the memorization can be a bit challenging.

But the use of the wooden donkeys-that-poop is the delightful heart of this game. Yes, it could have been any theme and just used boxes or some other container. But then no one would remember the game decades later.

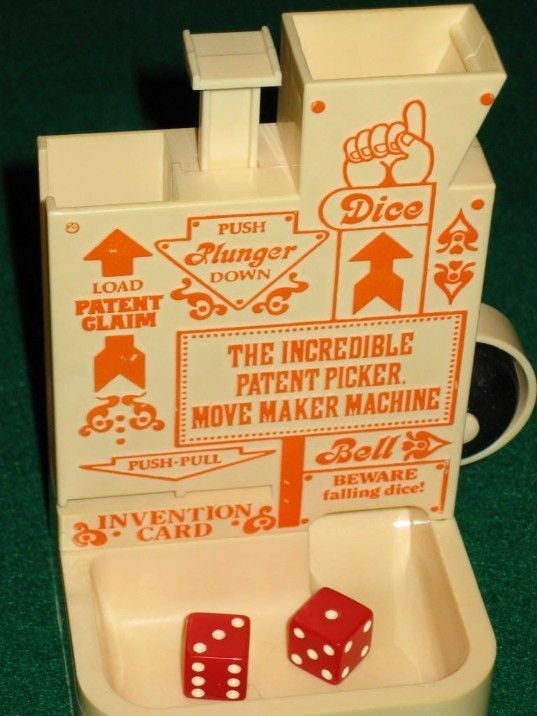

#1 The Inventors: The Incredible Patent Picker Move Maker Machine (1974, Jeffrey Breslow)

Seeing a picture of this relic of my childhood started me on the path of putting this list together, so I had to put it at #1.

I present to you The Incredible Patent Picker Move Making Machine:

This gadget performs two key functions in the game. First, it acts as a dice tower. You put the dice in the chute on the upper right, and push the lever. They drop through, hit the bell, and end up in the tray.

You can also use it to put ‘claim’ clips onto patents that you acquire. You load the clips into the chute on the upper left, and when you stick a card on the slot underneath a clip is attached to it.

This is from the game The Inventors, which is about zany patents through the years, so it is not only fun and toyetic, but is perfectly thematic. How fun is it to have a wacky invention in a game about wacky inventions!

Conclusions

So what have we learned?

When mentoring new designers, and working with people on their pitches, one thing I always stress is the importance of having a hook. How will the publisher sell your game? Why will a consumer buy your game over others on the shelf? Why will a reviewer want to cover it?

There are many hooks, including a unique theme or take on a theme, a mechanic, the artwork, the size or component count, or even the name. But it can also be a unique component.

And that’s what all these examples have in common. Here are games that have lived in my memory for decades because of unique features that made them stand out.

Obviously doing something like this isn’t the only way to stand out from the crowd. But it’s one that you might consider. And don’t be bashful about putting that front and center in your publisher pitch - assuming, that is, that you have some idea of how much it will cost to produce (or generally how it would be done), to show that you’ve done your homework and are not just being outlandish.

Plus keep in mind that it doesn’t need to be tied to the core mechanic. It can just be an unnecessary-but-cool extra that elevates your play experience.

Your Turn

In spite of my foolproof, completely objective selection process, it is slightly possible I’ve missed some of your favorite unnecessary components. What has made an impression on you? What makes your heart sing with joy? Please let me and everyone else know in the comments!

You say "completely unnecessary" here but I see it as "SOME designers that actually remembered that games are a form of play, and therefore you can design them as toys." Starfarers of Catan is the king of this and I'm surprised it wasn't on your list - you get these cool toy rocketships with tons of little plastic components to customize your rocket, and at certain points you get to pick up the rocket and shake it and put it down again! Completely unnecessary, mechanically speaking - they could've had a board with starship stat trackers and a single die with color combinations on it - but oh boy did they understand that the first thing anyone does when learning the original Catan is to build some kind of structure out of their roads, and lean into that.

Mousetrap is also the obvious place my head would go for this. The contraption you built never seemed to actually work properly, and it served no mechanical purpose, but without it you'd be stuck with a completely nondescript roll-and-move.

I've thrown some shade at Knizia for how ridiculously overproduced Lost Cities was, but dang if it isn't a gorgeous game with great hand-feel.

When I taught game design, I would definitely talk about this, how the choice of components to use in boardgames should be a *deliberate* choice. Mathematically, there's no difference between dice, a spinner, a teetotum, or a deck of cards where you draw then replace; UI/UX-wise they are entirely different experiences to interact with. Often the consideration is just how to make the components as cheaply as possible. Sometimes it's what produces joy to touch and feel and play with. Knowing which components to sacrifice for a lower cost and which to fight with the publisher over because it's a necessary and memorable part of the experience... is game design.

Bilionaire was fun game as a kid. You're right about the spinners - lots of fun to flick them as hard as you can to get them to spin a long time. But I really liked the carbon pads the most - no messy cleanup and worrying about pens drying out. When I gave it away a few years back, everything still worked!