I enjoyed the Marvel series What If, even though it's a bit uneven. The last episode - "What If... Thor Were an Only Child?" was a particular favorite.

Saturday Night Live used to have a running bit called "What If" that considered such questions as "What if Spartacus had a Piper Cub?" The only clip I was able to find online was "What If Superman had landed in Germany?"

In a related vein there was an excellent 3-issue comic series called "Superman: Red Son" which assumes Superman landed in the Soviet Union.

Exploring "What If" is one of the interesting aspects of simulation games. What if the Germans moved their forces from Calais to Normandy before D-Day? What if Stonewall Jackson had survived to be with the Confederate army at Gettysburg? What if the Warsaw Pact had attacked Western Europe?

Counterfactuals

Dealing with these counterfactuals demands a lot from the designer, in terms of knowledge, research, and game design.

I've been thinking about this intently as I've been working on a new design. I can't give details yet, but it is based on a historical situation. (Note: I was referring to the game Zheng He, which is now on the GMT P500. I also discussed this in the last newsletter on Game Budgets).

When creating a model for a historical event, the most important thing, of course, is to make sure that what happened historically is a possible outcome from the game. If it is impossible to recreate the historical result, the game will be criticized (rightfully, in my opinion).</p><p>However, how <u>likely</u> does the historical result need to be?</p><p>I haven't done a scientific survey - I'm not sure anyone has - but anecdotally I think almost all designers tune their models so that the most likely outcome is the historical outcome. You can think of the historical results of a game as creating a bell curve. The peak of this curve could coincide with the historical outcome.

he 'historical result' most easily correlates with the final result, and can be tuned with victory conditions.

For example, let's say you are designing a solitaire game about World War 2 in the Pacific, and the player is representing the Allied side. Most historians agree that once the United States entered the war after Pearl Harbor, it was going to be very difficult for the Japanese to win. This may not have been clear at the time, but it is in hindsight.

A natural victory condition for the designer is how quickly the Allies can end the war. It's not the only option, but it's a straightforward design choice. Historically the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. As a designer, I can tune the game so that most of the time the player wins in August, and achieves the historical result. Then perhaps I set the victory condition to be winning faster than was done historically.

Is this reasonable from a historical perspective? If you were to rewind history and replay the war hundreds of times was August 45 the average? Or maybe it was earlier or later than the 'average' result? Maybe it actually looks like this?

Of course, we can't know. This is where the research and judgement of the design enter the picture, along with - very strongly - their point of view, or 'authorial hand' as it were. When you, as the designer, set those victory conditions, you are making a statement about whether you think that the actual participants could have done differently, or better, or worse.

The simplest thing is to just say that the historical outcome is the most likely. That takes a lot of the pressure off, but it can also be a bit of a cop out. If you do your research you should at least consider the alternative.

As I mentioned, I've been working on a new design, and I'm facing this issue head on. It's going to be a solitaire-only design, but the more I research and learn about the actual event, the more I am convinced that the historical result was all the way at the tail end of the bell curve. Pretty much everything went right. It's hard to point to any areas where things could have gone significantly better. Perhaps some of that is due to the nature of the historical record, which only wants to highlight the positive. But even so, I still think that's the case.

I am currently leaning towards making the historical result, in game terms, correspond to a very strong victory - something for players to strive for.

However, I need to make sure that this is clear through the design notes. The details of this event are not that well known, so many players will be learning about it for the first time. If I take this route, the history the players experience in the game most likely will not match up with what occurred. I feel a sense of responsibility to make sure the players are properly able to contextualize their in-game experience, and the history surrounding it.

Event Modeling

One of the more popular styles of wargame is the Card Driven Wargame (CDG). One of, if not the first example of this was 1993's We the People, designed by Mark Herman, my co-designer on Versailles 1919 and the upcoming Triumvir.

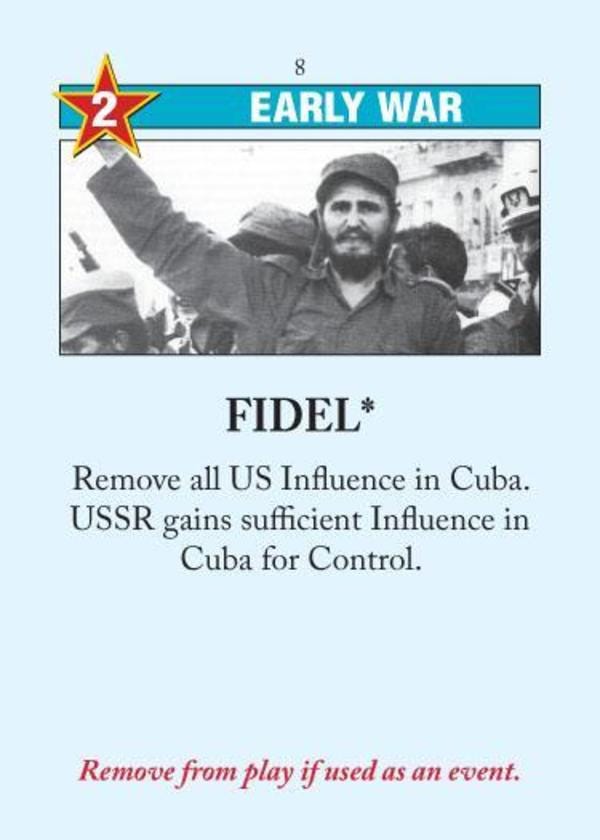

A key feature of CDGs, and one of the things that makes them so thematic, is that each card is a specific event from the time period. For example, here's the Fidel card from Twilight Struggle.

These historical cards do a terrific job of bringing the theme. Playing the Fidel card is much more evocative than just making a die roll to see who controls Cuba. It also allows the game (and the designer) to teach more history than it otherwise might. For example, there is a card with the event "Sadat Expels Soviets". Players may not know who Anwar Sadat was, or if they do, not know that he broke Egypt's ties with the Soviet Union. The history behind these cards can be discussed in the rules, and may inspire players to learn even more about the particulars.

However, in the game these events rarely occur in the order they did historically. They are evocative, but don't create a new historical timeline, truly. Some CDGs constrain when cards can be played, through breaking the cards up into certain time periods when they can be played, or requiring some cards as prerequisites for other cards. Twilight Struggle does both.

But this does not eliminate the fact that these events still are basically a jumble of unrelated facts, like shuffling a deck of flashcards.

Also, these games also only include events that actually occurred, or sometimes that were planned but never executed. They never include true counterfactuals. For example, again in the Pacific Theater of WW2, Japanese admiral Yamamoto was shot down while being flown over the Solomon Islands. This is represented by a card in Empire of the Sun. But there is no way, in the world of the game, that MacArthur can be killed.

On one hand, this makes perfect sense given the point of the card events. They are designed to educate, and give players a touchstone to connect the real history with what happens on the table in front of them. Also, if counterfactual events were to be included, the designer would have to fabricate them, some out of thin air. There would also probably need to be a way for the player to be able to distinguish between events that happened, and those that were invented.

On the other hand, though, including only historical events necessarily constrains the scope of the game and the 'what if' level that it can portray.</p><p>Please don't get me wrong - I thoroughly enjoy many, many CDG games, which also include the COIN (Counter-Intelligence) games like Cuba Libre (speaking of Fidel!). But this aspect of them always gives me the feeling of operating within a constrained sandbox.

Spinning to Infinity

One of the decisions we made early on during the design of Versailles 1919 was that the victory conditions would be based on what the historical personages represented wanted to achieve. Historically, going into the treaty negotiations at the end of World War I, France (and somewhat the UK as well), wanted very punitive measures against Germany. In the end that backfired, as it led to the collapse of the German economy and the rise of the Nazi party, and ultimately their conquest of France, but that wasn't known to the French at the time.

So to put the players in the shoes of the French, that was modeled in the game. The whole creating-the-conditions-for-World-War-2 thing is ignored in the game. Arguably the French "won" the Treaty of Versailles negotiations.

However, as a player you are remaking the world by hammering out the treaty. It is certainly tantalizing to see how your version of the treaty would impact world history going forward. At the very least, giving players that visibility would help the educational message of the game, that these decisions had consequences we are still wrestling with today.

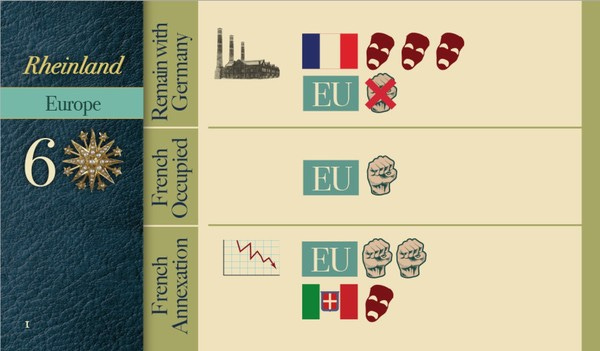

So while we were working on the game I started development on a fairly ambitious project - a post-game future-history simulator. The idea was this: Versailles 1919 is based around Issue Cards. Whoever 'controls' an issue gets to select which option shown on the card is included in the treat.For example, here's the card for the Rheinland:

Whoever controls this issue selects what happens to the Rheinland.

In my plan, after the game was over you would go to a website or app and enter in all the final choices that were made on these Issues.

It would then spin out an alternate history based on those choices, that would go, ideally, through the end of the 20th century.

There are two approaches I looked at to do this. One I called a scenario system. In this, I would write up a series of "short stories" - think of them plot summaries for "What If" episodes. Then, based on the selections of the players, the website would serve up one of these scenarios as the post-game report.

The other option I looked at was a procedurally generated simulation. Again, you'd enter the players' choices into a website. It would use those choices to build a 'state of the world' model in 1919. Then, it would simulate economic change, political stability, and more, year by year by year.

There are challenges with both. The scenario approach limits the possible result space, and collapses a lot of the decisions. If all the other decisions are the same, except that in one game Rheinland is left with Germany and in the other it is French occupied, that may not make a big enough change to shift it to a different scenario. That would be exacerbated by knowing that I would be limited in the number of different scenarios I could personally write. But maybe that would be enough given the number of times players would play the game.

In the end I chose to work on the second approach, procedural generation, with its shadow of Foundation and "psychohistory". I actually got pretty far on it and developed a model of economic and political instability that led to the coups, revolutions, wars, and the rise and fall of different alliances.

However, it was, in the end, really unsatisfying. One reason was that it was hard to create a narrative that tied everything together. But the main issue was that very small changes in the starting conditions actually led to really huge changes in the end state. There was a healthy batch of dice rolling under the hood - like whether there would be a revolution based on the level of political instability. I did have the starting state deterministically create a random seed, so that if you did exactly the same thing in the game, the simulation played out exactly the same way.

However, there was a huge "butterfly effect". If everything was the same but you chose a different Rheinland option, the future history that was created started similar, but rapidly diverged. I had created the mathematically definition of chaos - small changes in initial conditions led to huge, unpredictable changes in the future.

There was so much variability that it didn't feel satisfying to try a slightly different input. You felt that you had basically no control over what happened.

The Scenario method had too little variation, and Procedural Generation had way too much. Maybe there was some middle ground where I used Proc Gen, but kept it more on certain rails. But the whole project started to seem pointless.

In the end I gave up on having a Versailles 1919 post-game story. If someone wants to pick up the idea and run with it, that'd be very cool. But it really led me to do some deep thinking about what it means to have an 'alternate history'. I actually think that the butterfly effect of my Procedural Generation model is way closer to the 'truth' of alternate histories (whatever that means). But for our embrace of narrative flow and cause-and-effect it is very unsatisfying.

Designs that allow the players to explore alternate history need to balance these competing factors of keeping players constrained while still giving them a sense of influencing events. It is often a precarious balancing act, particularly as time frames and scopes expand. In History of the World the same empires will come up at the same times, game after game, for the most part. The Persians will come onto the world stage in Epoch II, the Chola in Epoch V, and the British in Epoch VII. But, of course, the chances of their having been a "British Empire" the way it happened if you rolled back the history clock are basically zero.

But sometimes sacrificing 'realism' for gameplay, particularly gameplay that fits player expectations, is the correct way to go.

Postscript

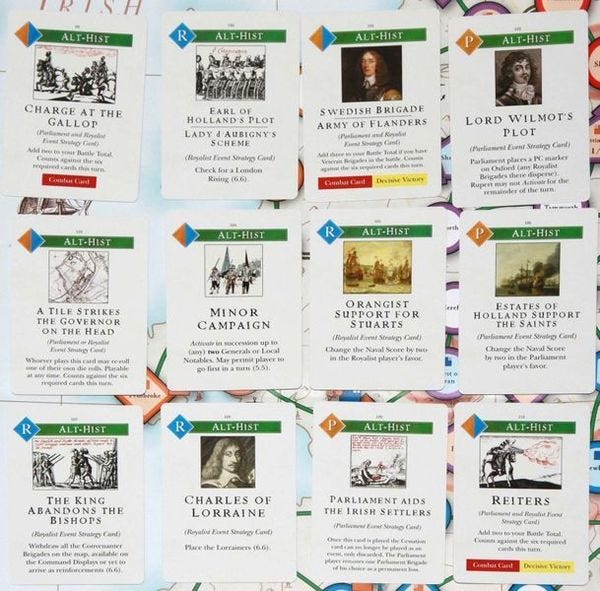

I got a lot of great feedback from readers about this newsletter when it was originally published. One of the things I expressed was that games that have event cards typically just represent events that occurred.

Several readers let me know that the game Unhappy King Charles actually has several Alternate History cards that do just this. Here's a picture of them.

I think this is really cool! I've played the spiritual father of this game, Here I Stand, and this feature really makes me want to try Unhappy King Charles.

I don’t get to play war games very often (I need better friends) but one game I play fairly often is Star Wars Risk, the version that’s not actually Risk but a TIE Fighter-shaped board modeling the battle at the end of Return of the Jedi. This is a simple game with a binary state: the rebels win, or lose -- unlike Zheng He, Stronghold or any other game where speed or margin matters. In my experience, the rebels win almost all the time, which matches the “historical” outcome, but makes for an unsatisfying game.

Great column! Your discussion of a "future history simulator" brings to mind Dice of Decision, the scenario generator for Totaler Krieg. Players work through a series of charts and die rolls, starting with the opening moves in World War I, to create a different world for the start of World War II. I keep thinking about how it could be converted into a game where the player(s) can apply points to try and change the die rolls in an attempt to influence the outcome. I haven't come up with a solution yet.