The Avalon Hill Game Company launched the modern wargame in the 1960’s. And one of their key marketing techniques was to put you in the shoes of history’s greatest generals.

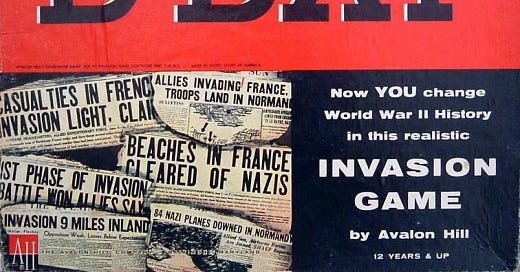

Today is the 79th anniversary of D-Day, so let’s take a look at the 1961 box cover of the game of the same name:

The font size choices tell an interesting tale. The game title, D-DAY is largest, followed by INVASION GAME. The next biggest is the YOU, in bold and all-caps.

Three years later they were still doing it. Here’s the 1964 cover from Afrika Korps:

Again, the YOU is all-caps and bigger than the other text. Not sure why they decided to put GAME in all caps, but not Desert Campaign, but that’s a mystery for another post.

Avalon Hill realized early on that giving players a hook to put themselves into the game, giving them a clearly defined persona, was a way to improve their experience, and the narrative that can be built.

One of the questions that I’m most asked about designing games is whether I start with a mechanic or a theme. In truth, most of the time I do neither. I start with an experience I want the players to have, which is a combination of emotion and narrative with the theme. For example, “Zombies” is a theme. But if someone tells me to design a Zombie game, that leaves way too much room to start doing anything constructive. Is the player in a single room putting up barricades until a helicopter arrives? A group traveling through the countryside to reach a safe-zone? Entire nations battling zombie hordes and each other? Until the theme gets combined with narrative, and the emotions you want the players to feel, I find myself just bumbling around.

And identifying who the player is – and making sure they know it – is key to that process. In those zombie games the player could represent a single person, a small group, or the leader of a nation. Regardless of which you choose it’s important that the players feel connected to that role.

Identifying who the player represents is a key to the design process

Take another look at the Afrika Korps box. It actually tells a story in the small text, between the icons:

Early in 1941, a general named Rommel, commanding Panzer Regiment 5 and other small units rolled across the British at remote El Agheila, swept the Western Desert under the German Cross and began the legend of the Afrika Korps

… and after 2 years of seesaw war against the Eight Army’s New Zealanders and Australians and Indians and Britishers and South Africans and French and Poles and many others, finally broke his sword.

This is such a great example of setting up the experience for the players. You’ve got two competing narratives here, depending on which side you’re playing. The first part (above the game title) tells a tale of a scrappy commander winning seemingly against the odds (small units) to become a legend. Then below the title it gives the story of the Eight Army player, which seems like the rebels from Star Wars coming together to overthrow the empire.

So both players have their role, and their experience handed to them right on the box cover.

As war games became more popular through the sixties and seventies, their role as simulations became more valued by players. They favored games with more realism, that incorporated many different aspects of the historical situation. Morale, supply, untested troops, weather, all became staples of wargames.

This quest for ultimate realism peaked on tactical end with Tobruk (1975) and on the strategic end with The Campaign For North Africa (1979). Tobruk included incredibly detailed rules for armor penetration, including how the relative angles between the armor plating on different makes of tanks, and direction of the shells arc impacted penetration probabilities. Campaign for North Africa was notorious for its incredible level of detail, tracking individual water rations.

But a funny thing happened. Everyone slowly realized that more detail didn’t equal more realism. And this goes back to where Avalon Hill started – Now YOU command. New designs remembered the YOU but forgot the COMMAND. It was clear who you represented in Tobruk or CNA – a platoon commander, or Rommel. But it forced players to deal with details that were well below what the actual commanders wanted to – or were able to – deal with. Monster games like Fire In The East had players move around thousands of chits, but no commander ever was concerned about specific unit placement down to that level.

Omniscience doesn’t equal realism.

The key challenge for the designer was creating systems that gave the appropriate scope to the game, that put the players in charge of what their counterparts would have been in charge of, give them the same knowledge, and the same tools to deal with the situation.

And that turned out to be a much more intricate and subtle problem. It was easy to just do more research on the Order of Battle, but quite another to create systems that convincingly simulate what is outside of the player’s control.

The venerable CRT is an early and classic example of this. The commander can get the right forces into the right place at the right time – but the details of what happens in that skirmish can’t be controlled. But modern wargames look for more novel ways to limit players omniscience and omnipotence.

Card-drive Wargames, like We The People and Hannibal, gave another mechanism for giving appropriate options to players. They present players with a controlled subset of options at any given time, and shield the exact responses their opponents will be able to make, creating a more realistic Fog of War.

The Command and Colors series gives players a hand of cards that limits what sectors of a battle they can ‘activate’ each turn. This was expanded on in the Combat Commander series, where the cards you have determine the orders you can issue.

Firepower was one of the first games that used a chit pull system to determine which units a player could give orders to, a system which has been used in many games over the years.

And the much-lauded Up Front puts the player in charge of several squads, but takes even knowledge of the geography the battle is being fought over out of the hands of the players. Some felt that this went too far, but Avalon Hill and the designer defended the design decisions to the hilt, ultimately winning over the wargaming community to this style of simulation.

The reality is that every war game has to abstract some elements. And knowing which to abstract, and how, is the key to great simulation design.

Limiting player control over what they know, what they can do, and how that can turn out, can emphasize the experience for the player, and their identification with their role. In my WW2 ETO game The Fog of War I specifically wanted to focus on the big picture of setting strategic direction, on par with what the national leaders or supreme field commanders faced. The exact location of a unit, and what was covered by its Zone of Control, wasn’t their issue. The concerns were what the overall strategy would look like, and trying to figure out the plans of your opponent. I also wanted to try to truly represent the hidden nature of surprise attacks and defenses that were hardened well beyond what the attacker anticipated. I’ve been gratified by the positive response to what is an admittedly unorthodox game.

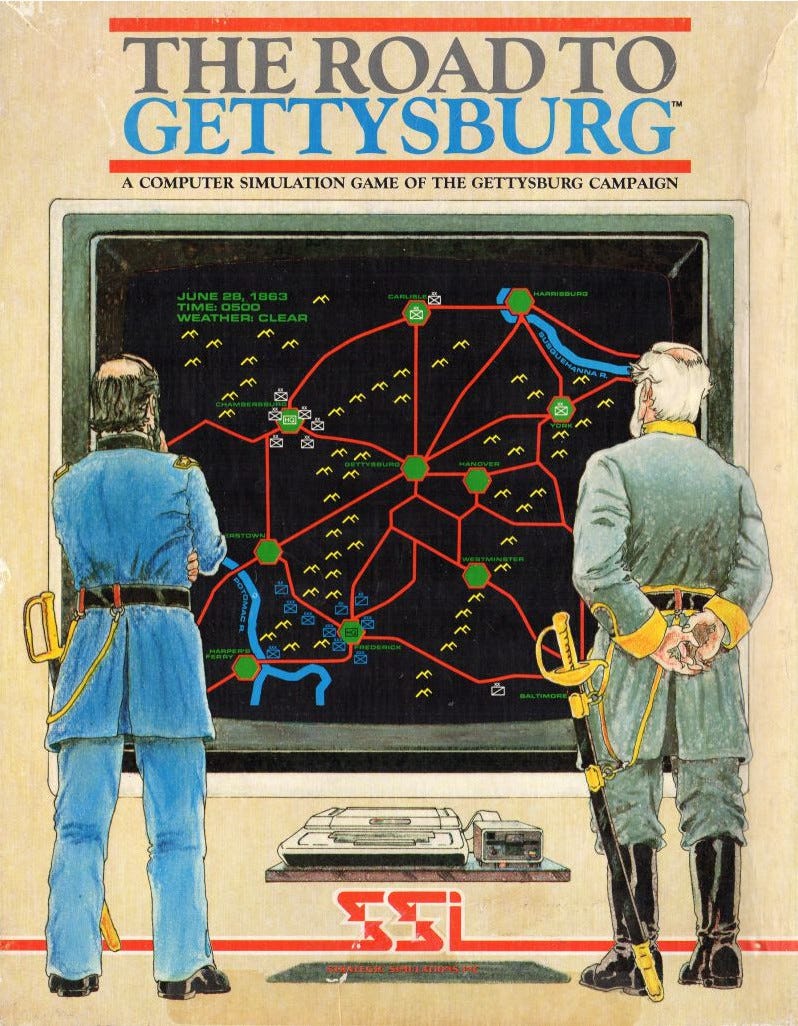

I’d like to wrap up by describing a little-known computer war game from the 80’s – Road to Gettysburg, by SSI. This brilliant game put you in the shoes of Meade or Lee and covers the maneuvering around the Pennsylvania countryside that led up to the battle.

The brilliant part of the game is the way you control your forces. You have to specifically send orders to your subcommanders – and those orders will take a variable number of turns to get to them. And depending on the leader they may take a while to act on the orders, or just ignore them completely. Or they may get intercepted by the opponent and never arrive.

And to add to the confusion, those leaders send you updates about what’s going on, but they also take several turns to get back to you. And some leaders tend to be serial exaggerators about the size of the opposing forces they see. You have a laminated map where you try to track the positions of your own and the opposing units, but it’s a best guess based on the latest dispatches you’ve received.

The 11 division report above is from 0500 hours. You probably received this around 0800 or later depending on where your HQ is. Are they still where they say they were, at 6,6? Have they marched on from there? Have they been attacked?

It is fog on top of fog, and it was an absolute delight to play.

You can actually play a version of the game via a browser emulator here:

https://archive.org/details/a2_Road_to_Gettysburg_The_1982_SSI_RDOS

but without the maps and rules it’s a little challenging.

This is a concept – sending messages to your commanders – that I would love to be able to incorporate into a tabletop war game design, but I’ve struggled with how to make it playable. But if I get it working, I think it would be incredibly immersive.

So the next time you’re playing a game, think about who you represent, and the techniques the designer used to put you in those shoes.

This reminds me of an exercise I participated in back in 1999 as part Prof. Eliot Cohen's class on Understanding Military Technology at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington DC. He used the computer game Sid Meier's Gettysburg, which was brand new at the time. Teams playing each side were set up in separate rooms with each individual sitting in their own computer booth. Each side had an overall commander and three or four subordinate commanders. Although the players each controlled their own individual units, messages between and among the commanders and their subordinates had to be hand written and delivered by a runner. In addition to the lag in executing orders built into the computer game, the hand written message system slowed down the players' actions and responses down even further.

As I recall, I was a subordinate Union player stationed near the south end of the Union line. We were in the process of improving our position and preparing to advance when the Union player at the northern end started messaging for help. He wasn't very specific, and we couldn't see what was happening. Before we knew it, the Confederates had conducted a massive sweep around our right flank and rolled up our line. We were destroyed piecemeal before we could establish a new defensive line facing their attacks. A vivid lesson on the fog of battle in the 19th century!

Geoff, do you have any plans to reprint/remake Fog of War? Possibly in a different setting than WW2?

I find it very hard to play WW2 games. They usually mean that either me or someone I'm playing with should control Nazi Germany forces, and try to help them win. This makes me feel really unconfortable. I'm fine with controlling Orcs or Necromancers or any other fantasy "bad guys", but WW2 is too real.