I’ve been following the situation with Powerboats and Joyride. For those of you that are unfamiliar, here are the broad outlines:

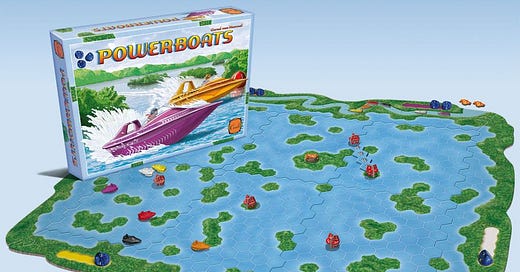

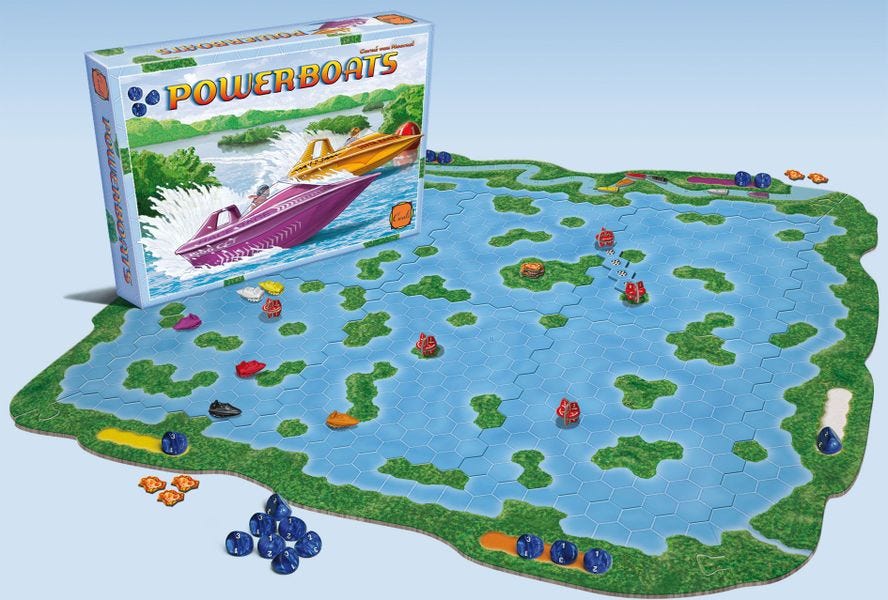

Powerboats was published in 2008 by Cwali. A few years ago, publisher Rebellion Unplugged (“Rebellion” for the rest of this article) reached out to designer Corné van Moorsel about doing a reprint. They were unable to come to terms and a few years later Rebellion published Joyride, which is clearly based on Powerboats, but also clearly has some new elements added.

Several people reached out to the Tabletop Game Designers Association (of which I am the current President) to ask if we have a response or formal position. We are still formulating one in consultation with our board and members, but I wanted to share my own thoughts.

I have not evaluated the rules of both games to see how similar or different they are, but even if I did, the question of ‘copying’ another game vs ‘being inspired’ by one is a continuum.

The growth and innovation we have seen in the board game industry has been driven in part by designers building on the work of other designers.

Regardless of whether designers or publishers believe they should be able to own or protect a specific mechanism, the US court system has already ruled that mechanisms are not protected by copyright. In 2016 a clone of Bang was published by another company, with no license or compensation to Bang publisher Da Vinci.

Court rules in favor of cloned tabletop game - No protection under US copyright law

Art, the game title, and specific rules wording or terminology can be copyrighted, but not the underlying core of the game.

Protection of ideas is still available via patents, but that is an expensive route and can be difficult to obtain for game mechanics.

So Rebellion Unplugged is legally allowed to do what they have done, at least in the US. I’ve started conversations with knowledgeable folks in the EU and other countries to see if there are differences in the law.

Now whether it’s morally acceptable is a separate question.

Joyride definitely adds some elements to Powerboats. Whether that is ‘cloning’ or ‘inspiration’ is going to be a decision for each individual. It is impossible to quantify how ‘different’ a game needs to be before it is not a clone. This type of thing arises with patents, and it is challenging for courts to decide whether something infringes on a patent or not. We don’t have courts to fall back on in this case, so it will be up to the public.

However, it is clear in this case that the designer/publisher was aware of Powerboats – they tried to license it initially. Given that it was so clearly based on that game, the publisher should have given a credit of some type to the Powerboats designer in the rules and wherever the design is discussed. Powerboats is only mentioned in passing in the Designer Diary posted on BGG. That would have been one opportunity to give credit to van Moorsel. Mentioning it in the rules would have been another.

Celebrating designers should be a cornerstone for both publishers and designers. Rebellion Unplugged absolutely failed to meet that standard.

Tropes and Clones (Clone Tropers?)

I have seen several comments about this issue that say that it is OK to include ‘tropes’ like Deckbuilding and Worker Placement in a design, but not ‘original concepts’.

I feel that this is misguided. Deckbuilding was absolutely an original concept when it came out. It only became a trope because so many people copied it. The first few iterations on deck building after Dominion were things like ‘Dominion plus combat’ or ‘Dominion with survival’. Again, there is no objective (or legal) standard to decide how different something needs to be to be in the clear.

Another celebrated case of ‘inspiration’ flying too close to the sun is David Sirlin’s Flash Duel, which was based on Reiner Knizia’s En Garde. The core of Flash Duel is clearly En Garde. Sirlin added a slew of characters, each with their own special cards and abilities. Was this enough to make it not a knock-off? Again, everyone will need to make their own decision.

Where Sirlin objectively did fall down was in not crediting or acknowledging En Garde in any way. If he had, perhaps the furor that arose from Flash Duel would have been more subdued.

A counter example is the game Witchstone. As a core mechanic it uses the tile placement from Knizia’s Ingenious. Designer Martino Chiacchiera reached out to Knizia to ask for permission to use the mechanic in his game, and ultimately Knizia was listed as a co-designer. I am unaware if there was any financial arrangement.

I have played both Witchstone and Ingenious, and honestly I did not make that connection when I played the former. I have to admit that if I had designed Witchstone, while I would have given Knizia and Ingenious credit, I would not have reached out to him beforehand for permission. Perhaps initially the designer thought that his game would be more of an Ingenious clone than it turned out to be.

Either way, hats off to Mr. Chiacchiera.

Protecting Your Design

In terms of designers being concerned about protecting their designs, there are a few considerations:

The Joyride / Powerboats issue is a case of a designer/publisher using an already-published game (as mentioned, Powerboats came out in 2008). While the publisher and designer did have contact prior to the publication of Joyride about a reprint, this is not an example of a publisher taking a game pitch and publishing it on their own.

This is more akin to the aforementioned Bang / Legend of the Three Kingdoms situation, which has happened a few times. Tok Tok Woodsman and Bamboo Bash, or Deflexion and Laser Chess are other examples. However, it is rare. Legally there is no way to stop this (although Deflexion had a patent, which helped them).

When submitting a sell sheet or idea to a publisher, many designers have concerns that their idea will be stolen. While it has happened, this is exceedingly rare. And any reputable publisher will not do this, as there are tons of new ideas, and publishers would rather have the designer on board than risk bad publicity.

There have been cases of ‘convergent evolution’, where companies are working on a design and a similar one is submitted, or they learn that one is being worked on. An example is The Insider (Oink) and Werewords (Bezier). (more details on this here Bezier founder responds to Werewords ‘copying’ controversy - Tabletop Gaming)

Larger companies, like Hasbro, will have designers sign an agreement prior to a pitch where it says, among other things, that they may be working on an idea internally already, and if so you pitching a similar idea does not give you any claim on it.

Some designers like to do the reverse, and have publishers agree to Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) prior to showing an idea, but most publishers are resistant to this. They see so many ideas, that the extra step of reviewing a legal document before every pitch is not worth the trouble.

Non-Compete Clauses

Here’s another angle. I have seen several licensing contracts with publishers that have a clause like this:

Non-Compete Clause: During the term of this Agreement, [the licensors] agree not to license or develop a game with similar mechanics for any third party.

I understand the intent here. My Super Skill Pinball is inherently ‘skinnable’. I can see that WizKids would be annoyed if I just designed some other tables using the Super Skill Pinball system and published them with someone else, unless we had discussed that possibility in advance (NOTE: The above clause is not from my contract with WizKids).

But the question this raises of course is - what are “similar mechanics”? If we go by Board Game Geek, “Hand Management” and “Dice Rolling” are mechanics. Surely I’m not enjoined from making another game with dice, right? But how far does that go? Super Skill Pinball uses a base system where you roll two dice and choose which one to use. Should I not be allowed to use that in another game?

When I see this clause in contracts I’ve been recommending that it be changed to “substantially similar”. That’s better, but it still leaves a lot of room for judgement. But honestly I’m not sure how to define that. Some contracts say the designer can’t publish other games that “compete” with the one being signed, but all games compete with each other on some level.

So again, I understand what the publisher is looking for, but I have no clear idea about how to express it.

Being a Good Neighbor

The bottom line is that it’s very hard to draw an objective line about what is acceptable or not. There are things that are clearly bad, and others that are clearly OK. But there’s a big gray area in the middle.

We always say that game design (and the hobby in general) are a community. Part of being a community is being a good neighbor, which means being considerate and respectful.

At a minimum designers should cite their sources and inspirations. The Dragon & Flagon, designed by my family, was absolutely inspired by the 1980 game Swashbuckler. If you played both you can clearly see the DNA - programmed movement and thrown mugs hitting people in the head making them fall off a table being two examples. But there are many differences between the two as well, and I don’t think we could be accused of being a clone. I know that whenever I talk about the game I mention Swashbuckler as an inspiration, but I could not remember if we actually cited it in the rules. I went back, and was pleased to see that we had:

The designers would like to acknowledge Thomas O’Neil and S. Craig Taylor. Their 1980 game Swashbuckler provided the spark that launch the design of The Dragon & Flagon.

You should always ask yourself - what would Mr. Rogers do?

Ultimately information, publicity, and the court of public opinion are going to be the best defenses to the very rare cases of bad behavior from publishers and designers.

Thanks for bringing so many historic examples into the discussion when exploring this, especially important in a field that's not always super well documented. It's fascinating to look at how this problem has been dealt with, and that it has been an ongoing puzzle within gamedev. I do absolutely hope, as you suggested, folks see the value in being good neighbours.

Ah, I remember hearing about the Flash Duel situation many years ago. Apparently Knizia had kind of a history of threatening (groundless) lawsuits over reuse of game mechanics, and the decision not to include the originally intended credit with Flash Duel was based on a recommendation from a lawyer, on "just in case" better-safe-than-sorry grounds. My impression is that it's one of those situations where no one was really happy with the outcome.

Although, well, absent the story surrounding Flash Duel, I don't think anyone would ever even talk about En Garde anymore to begin with — the game feels kind of like an experimental movement mechanic, packed up and sold in a box, and Flash Duel kind of feels like "what if En Garde were a completed game design." It's kind of a frustrating situation all around, especially given that the reimplementation is just a significantly better game.